I've mentioned this before but the law reports can be a great source of local history that might otherwise be lost. Another case in point is MacKenzie v Bankes in 1877 which concerned fishing rights in a loch in Wester Ross.

|

| 360 degree view by Dave Lawson here |

Despite being set amongst the most dramatic scenery, Dubh Loch - the nearest in the photo above - is not well known. That's probably because it's a ten mile walk from the nearest road: in the starchy Victorian language of one of the judges in the case I'm going to talk about, it lies east of Loch Maree "in a very wild part of the hills, far from any gentleman's house". Dubh Loch is separated from its much larger neighbour to the north west, Fionn Loch, by a shallow bar or submerged ithsmus about 100 yards wide and covered with knee deep water between two spits of land. This feature is called A' Phait which is the Gaelic word for ford or stepping stones (thanks to my Gaelic consultant there - you know who you are) and it's crossed by a narrow stone causeway.

|

| A' Phait, with Fionn Loch to the west (left), as shown on the 1875 Ordnance Survey 6 inch map. You can see more of this map on the National Libraries of Scotland website. Use the "Change transparency of overlay" slider on the left to reveal high resolution geo-referenced aerial imagery under the map. |

|

| The causeway at A'Phait viewed from the south with Fionn Loch to the left and Dubh Loch to the right - picture credit Stuart S via Tripadvisor |

Incidentally, Dubh (pronounced "Doo") Loch means literally Black Loch and Fionn (pronounced "F-yawn") Loch means literally White Loch. However, the names are more figurative: Dubh Loch is black in the sense of being more often in the shade due to its surrounding mountains whereas Fionn Loch is white in the sense of being more often in the sunlight due to its more open aspect.

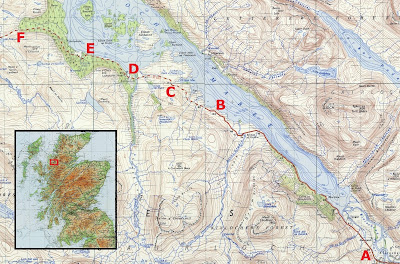

Anyway, before we get to the court case which embroiled Dubh Loch in the 1870s, we need to have a quick legal lecture: here comes the science bit - concentrate! as Jen A used to say in the shampoo ads. In Scottish law, if a loch (and I'm talking about freshwater lochs here, different rules apply to sea lochs) is entirely surrounded by a single property, then the owner of that property has the exclusive right to fish in it. But if a loch is bounded by two (or more) properties, then both (or all) the proprietors are allowed to fish in it. Moreover, each is allowed to fish in all parts of the loch - they're not confined to fishing just the part of the loch opposite their particular property. Applying that rule to Fionn and Dubh Lochs in the 1870s, look at the map below (click to enlarge):-

Both lochs were entirely surrounded by Letterewe Estate belonging to Meyrick Bankes (of a rich Lancashire family you can read about here) except between points A and B which adjoined Kernsary Estate belonging to Osgood MacKenzie (he who is most famous for having founded Inverewe Gardens).

Osgood and his guests and sporting tenants of Kernsary had been in use to fish over the whole of Fionn and Dubh Lochs for many years until October 1876 when Bankes put a stop to Kernsary fishing Dubh Loch, he being concerned, apparently, that fishers on the loch might disturb deer on his surrounding Letterewe Estate. Osgood responded to this by raising court proceedings to have it declared that he had a legal right, jointly with Letterewe, to fish in Dubh Loch. To succeed in this, Osgood required the court to find that Fionn and Dubh were all one loch. Because if it found that Dubh was a separate loch from Fionn, then, because no part of Kernsary adjoined Dubh, it would have no right to fish it and Bankes would be quite within his rights to prevent Kernsary from doing so.

|

| Osgood MacKenzie. I couldn't find a picture of Meyrick Bankes |

After a lengthy proof (hearing at which the evidence of witnesses is heard), a judge of the Court of Session in Edinburgh ruled in favour of Osgood MacKenzie by deciding that Fionn and Dubh were legally all one loch. He seems to have been influenced by scepticism of the evidence of Meyrick Bankes' scientific witness, Mr Buchanan, that A'Phait was really a river, albeit a short one, between the Dubh and Fionn and thus they were in no different situation from two lochs linked by a longer river. But observing that this so-called river was almost as wide as it was long, the judge dismissed this as "really a thing of the imagination".

Meyrick Bankes appealed to the Inner House of the Court of Session (Scottish equivalent of the Court of Appeal) where the matter was reconsidered by three senior judges headed by the Lord Justice Clerk. Taking a less scientific and more common sense approach, they decided that Fionn and Dubh were two separate lochs. Two of the judges were influenced by the simple fact of them having different names: in the words of the Lord Justice Clerk "these two sheets of water are as separate in their nature as they are in their names". The third judge was a bit doubtful about that - he observed that bits of the Mediterranean having different different names (Adriatic, Aegean etc.) didn't make it any less one sea - but he didn't feel strongly enough about it formally to dissent from his brethren.

Having lost the second set, so to speak, Osgood appealed to what was then the highest court in the land, the House of Lords (nowadays the Supreme Court). Though not without misgivings on the part of two of them, four law lords ruled that Dubh and Fionn were separate lochs. They were influenced by the consideration that what gives rise to the rule that a proprietor adjoining a loch is entitled to fish over all of it and not just the part opposite his property - that it's not easy in practice to identify where such imaginary dividing lines lie when you're out in a boat - simply didn't apply to Fionn and Dubh Lochs. It was perfectly obvious where the dividing line between them lay at A'Phait, even before the causeway had been built, where the evidence of the witnesses was that the water was not deep enough for a boat with a fisherman and a ghillie to pass over it.Thus did Osgood MacKenzie ultimately lose his marathon legal battle to get to fish on Dubh Loch. Legal fees must have been cheaper in these days because for the cost of a court case pursued all the way to the Supreme Court today, you could just about buy Letterewe Estate! Anyway, the legal outcome is less interesting than some of the nuggets of local history revealed by the evidence of the witnesses led in the case. Unfortunately, not all of the evidence is transcribed in the law report, only so much as the judges thought particularly relevant (which is great for lawyers but rubbish for historians!), but here's some of it. First, John MacKenzie, one of Osgood MacKenzie's witnesses, who built the causeway in 1828:-

"I put the stones there by orders of Duncan MacRae, tenant of Inveran, which was part of Kernsary. MacRae was also tenant of Carnmore [the land on the north east side of Fionn and Dubh Lochs] and Strathnashellag [a glen parallel with the lochs to the north east], on the north side of the loch. He told me to make a causeway or stepping-stones across the Phait. I got £5 for doing so. I used no lime or clay in making the causeway. I made it just of loose stones, not dressed in any way. Macrae ordered the causeway to be made to get sheep across the Phait from his one farm to his other farm. I cannot say very well what was the height of the causeway above the ground; I believe it was between 2 and 3 feet. The breadth, I believe, was between 6 and 7 feet."

|

| Looking down on the east end of Fionn Loch and Dubh Loch from the top of Beinn Airigh Charr. Picture credit Tim Allott |

My father was managing partner in the firm of Messrs Birtwhistle, who had the farm of Letterewe and some other farms in that neighbourhood. He was so at the time I was born, and continued to be so until his death in 1827. I was born at Letterewe. I lived there till I was twenty years of age, when I went into the navy as a midshipman. I remained in the navy till 1822. I then returned to Letterewe, where I spent two years. I next went to Liverpool, where I was for thirty-three years. I came back to Poolewe in 1860, and have been living there ever since. The first time I visited the Fionn Loch was in 1813. There were some smugglers then on an island in the loch, and they had a boat and took me across with them. I first saw the Phait in 1816. There was no artificial causeway across it in these days, so far as I observed. A medical student was along with me, and when we came to the Phait he carried me across the water. ... My father had a coble [flat bottomed boat] at the Phait at one time. I recollect that from the circumstance that one day a cattle-dealer named Peter Morrison was crossing the Phait in the boat. I don’t know how it happened, but the boat drifted out with him, and he got so much alarmed that he was shouting out to us how his property was to be disposed of. ... My father at one time kept a shepherd who kept a pair of stilts to go through the water."

A final interesting snippet came from Murdoch MacLean, born in 1788:-

"I have seen a boat on the Fionn Loch a good bit from the Phait. The man who lived in Kernsary owned it. It was kept to bring wood from the islands."

This evidence paints a fascinating picture of this remote corner of Wester Ross in the first half of the 19th century: vast sheep farms covering the whole hinterland between Loch Maree and An Teallach, some tenanted by locals, we may assume from a name like MacRae, but others tenanted by Englishmen, we may equally assume from a name like Birtwistle, in partnership with Scots. Note the reference to the witness MacIntyre's father having been the "managing partner" at Letterewe Farm - does this infer that Birtwistle was a sleeping partner, an investor in the booming wool and mutton business? Had he ever even been to Wester Ross? A cattle dealer venturing out of his comfort zone and giving himself a big fright by getting quite literally out of his depth in these wild places. Social mobility in the form of MacIntyre joining the Navy then living in Liverpool for 30 years before retiring to Poolewe. Friendly smugglers living on islands and shepherds on stilts! And all this in a landscape so barren that the only wood to be had is also on an island in Fionn Loch, the only place where the tree saplings are safe from being eaten by deer and sheep. (There's still a tree covered island in Fionn - picture here).

|

| National Libraries of Scotland - click the link and use the "Change transparency" slider on the left to reveal the underlying aerial imagery |

I've heard it said there were no Clearances in Wester Ross. But the Roy Map pictured above, drawn 1747-55, shows settlement and cultivation in Strath na Sealga and these people would have to have left, probably at the end of the 18th century, to make way for the sheep farmers. How much of a difference is there really between a "Clearance" in the sense of people being forced out by sheriff officers and having their homes burnt behind them as in Sutherland and those who simply saw the writing on the wall that said they couldn't afford the sorts of rents being offered for their farms by people bankrolled by the Birtwistles of this world and quietly, and without fuss, moved away from the land their ancestors might have occupied for generations?