Tuesday, December 8, 2009

Stromeferry - Part 2

In 1858, Inverness was connected by rail to Edinburgh and Glasgow (linked to London since 1849) albeit by a circuitous route via Aberdeen. In 1863, a more direct route via the Drumochter Pass was opened by which time railways also now extended north from Inverness up the east coast as far as Invergordon. But so far there was no railway to the west coast of Scotland north of the Firth of Clyde.

That began to change in 1865 when an Act of Parliament was passed incorporating the Dingwall and Skye Railway Company with power to build a line from the existing railway up the east coast at Dingwall to what is now the village of Kyle of Lochalsh. The promoters of the new railway were mainly influential landowners along the route and in Skye and the Outer Hebrides. In a speech to a meeting in 1864 appealing for subscriptions, the chairman, MacLeod of Dunvegan on Skye, made a telling point about travel in the north west Highlands:-

"You are all aware of the very little communication which exists betwixt the west coast and the town of Inverness. This town is undoubtedly the county town, but, at present, I call Glasgow my county town because I go there for everything I want by means of the steamers"

In other words, it was as easy to get from Dunvegan to Glasgow by MacBrayne's steamer (a distance of 150 miles as the crow flies which took the steam ship more a little over 24 hours) as it was to get to Inverness half the distance away overland.

One of the most graphic accounts of journeying from Inverness to Skye in the early 1860s before the railway is given by Alexander Smith in his book A Summer in Skye. He first had to catch a coach at 4.00am for the two hour drive to Dingwall. His record of this experience is worth repeating in full.

"There is nothing so delightful as travelling on a stage coach, when you start in good condition, and at a reasonable hour. ... On the other hand, there is nothing more horrible than starting at four A.M., half-awake, breakfastless, the chill of the morning playing on your face as the dewy machine spins along. Your eyes close in spite of every effort, your blood thick with sleep, your brain stuffed with dreams; you wake and sleep, and wake again; and the Vale of Tempe itself, with a Grecian sunrise burning into day ahead, could not rouse you into interest, or blunt the keen edge of your misery. I recollect nothing of this portion of our journey save its disagreeableness; and alit at Dingwall, cold, wretched, and stiff, with a cataract of needles and pins pouring down my right leg, and making locomotion anything but a pleasant matter.

Finding that all space on the mail coach from Dingwall to Skye had been booked by a visiting aristocrat for his servants, Smith was forced to hire a dog-cart (open horse drawn carriage) and driver. The horse supplied was not a good one, however, and to add to his misery, it started to pour with rain half an hour from Dingwall. At the first staging post (place to change horses), probably Achnasheen although he doesn't name the place, Smith was appalled to discover that travellers passing earlier had taken the only horse the inn possessed. Forced to stick with the same horse, and still raining, Smith decided walking directly across a stretch of moor and letting the carriage catch up with him round by the road would be preferable.

He reached Lochcarron in the late afternoon where the landlord of the "primeval inn" procured him a small sailing boat and crew. Dark and with the weather now alternating between calm and squalls, the crew gave up hope of reaching Skye and, past midnight and soaked to the skin, they put in at Plockton where he had to wake the inn-keeper. The boatmen promised to take Smith on to Skye the next morning but despite having been paid the full fare and money for accommodation in Plockton, they did not appear the following day. Fortunately, it emerged that the minister of Plockton was an old university friend of Smith's and he lent him his dog-cart to get to the ferry at Kyle, a drive of less than two hours.

The whole journey had taken more than 24 hours. Although MacLeod of Dunvegan doubtless made sure of a place on the mail coach if travelling to Inverness (about 12 hours from Kyle), it's easy to understand why he found it just as convenient to go to Glasgow by steamer (24 hours, overnighting in a cabin on board) and why he was vocal for a railway from Kyle to Inverness which would cover the distance in about 4.5 hours!

To be continued ...

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Renfrew - the airport that disappeared

Although abandoned, the terminal building and control tower remained standing for many years and I remember seeing it driving past on the M8 motorway (which was built almost along the line of the main runway) in the 1970s. It was finally demolished in 1978, I believe, and the inevitable Tesco now stands on the site. Most of the rest of the airport has been built over by houses.

Although abandoned, the terminal building and control tower remained standing for many years and I remember seeing it driving past on the M8 motorway (which was built almost along the line of the main runway) in the 1970s. It was finally demolished in 1978, I believe, and the inevitable Tesco now stands on the site. Most of the rest of the airport has been built over by houses.

Flying at what was originally known as Moorpark Aerodrome is believed to have begun as early as 1912 but the site was requisitioned during World War 1 to form an airfield for the testing of aircraft built at nearby factories. Military flying activities were moved to Abbotsinch (the site of the present Glasgow Airport) in 1933 whereupon Renfrew developed as Glasgow's civilian airport. I believe the first scheduled service was to Campbeltown that year.

Flying at what was originally known as Moorpark Aerodrome is believed to have begun as early as 1912 but the site was requisitioned during World War 1 to form an airfield for the testing of aircraft built at nearby factories. Military flying activities were moved to Abbotsinch (the site of the present Glasgow Airport) in 1933 whereupon Renfrew developed as Glasgow's civilian airport. I believe the first scheduled service was to Campbeltown that year.

Note - if you click the following pictures, they should link to the websites where I found them and where there are in most cases further pictures and extra information. Due credit to the respective photographers and thanks for their info.

The first picture below shows a row of Scottish Airways De Havilland DH89 Dragon Rapides outside the original terminal building in the 1930s.

There was military activity at Renfrew again during WW2 but this ceased after the war and, by 1948, it was the UK's third busiest airport and a new terminal building was required. This striking futuristic building designed by Scottish architect, Sir William Kininmonth, with its distinctive parabolic arch, opened in 1954:-

In the picture below of the airport viewed from the west looking east, the terminal building is at the top left:-

In the picture below of the airport viewed from the west looking east, the terminal building is at the top left:-

[EDIT - Here's a link to a late 1950's/early 1960s large scale OS map showing the 1954 terminal: click here.]

Despite its arresting architecture, Kininmonth's building of 1954 was destined to be Glasgow's air terminal for only 12 years. Air traffic grew massively in the late 50s/early 60s but it was impossible to expand Renfrew as the site was constrained by surrounding developments. Hence Glasgow Airport was moved to Abbotsinch which had been a Fleet Air Arm station (HMS Sanderling) since 1943 but closed in 1963. Apparently the 1954 terminal had been built at Renfrew with the intention of eventually demolishing it and rebuilding it at Abbotsinch. But traffic had grown beyond all expectations so a new terminal was required there and Kininmonth's masterpiece was redundant: the last flight departed on 1 May 1966 with operations beginning at Abbotsinch the following morning.

Renfrew Airport was gradually built over, the M8 motorway along the main runway in 1968. But as the terminal building and control tower were not demolished until 1978, they stood empty for as many years as they had been in use. Here are some pictures in the abandoned/demolition phase.

The picture above shows the terminal from the airside - the concrete on the right is the apron where the planes used to park. In the picture below, you can see the famous parabolic arch lying forlornly on the ground:-

The picture above shows the terminal from the airside - the concrete on the right is the apron where the planes used to park. In the picture below, you can see the famous parabolic arch lying forlornly on the ground:- Nowadays, there nothing left to see of the airport at all except that, even into the era of Google Earth, there was a bit of concrete left just east of the High School which was once the north end of the apron:-

Nowadays, there nothing left to see of the airport at all except that, even into the era of Google Earth, there was a bit of concrete left just east of the High School which was once the north end of the apron:- But to judge by current GE imagery (see above) even that seems to have gone now and been dug up and laid down to grass (and the trees cut down apparently). One of the few reminders of the airport is that there was once a nearby housing estate where the streets were named after airliners of the time but as a result of later re-development, Viscount Avenue seems to be the only survivor of these now.

But to judge by current GE imagery (see above) even that seems to have gone now and been dug up and laid down to grass (and the trees cut down apparently). One of the few reminders of the airport is that there was once a nearby housing estate where the streets were named after airliners of the time but as a result of later re-development, Viscount Avenue seems to be the only survivor of these now.And finally, I'll leave you with a really extraordinary picture. Rangers fans greeting their team's return to Renfrew in 1962. But not just thronging the airport viewing terrace (remember them?) - running out over the tarmac to the plane!

And finally finally (!), here's the nearest we'll ever get nowadays to a pilot's eye view of Renfrew Airport. The M8 looking west about a third of the way down the old runway 08, about directly opposite the terminal building (90 degrees over your right shoulder) courtesy of Google Maps street view:-

And finally finally (!), here's the nearest we'll ever get nowadays to a pilot's eye view of Renfrew Airport. The M8 looking west about a third of the way down the old runway 08, about directly opposite the terminal building (90 degrees over your right shoulder) courtesy of Google Maps street view:-

Sunday, November 1, 2009

West Tarbert Pier - Part 2

In October 1969, the Government perfomed a volte face. Citing the changed circumstances of the amalgamation of MacBrayne's into the STG, the Escart Bay scheme was abandoned. Instead, MacBrayne's would continue to operate from WTP with a spare CSP hoist-loading car ferry. The ro-ro ferry which MacBrayne's had ordered for the new Islay service (and which was nearing completion) would be used elsewhere on the MacBrayne's/CSP network.

The 1939 steamer MV Lochiel sailed for Islay from WTP for the last time on 17 January 1970 and was replaced the following day by the CSP's first ever car ferry, the MV Arran of 1954.

Above - the Arran at WTP. Picture by kind permission of "hebrides"

Above - the Arran at WTP. Picture by kind permission of "hebrides"In abandoning the Escart Bay scheme, it's hard to avoid the conclusion that the Government was toying with the idea of handing responsibility for the Islay services over to Western Ferries but wasn't quite able to take the plunge. As well as concerns about whether WF - whose services were rather more geared to freight traffic - could be trusted to have the long term staying power to provide a lifeline ferry service, there was no doubt an element of ideological hostility from a Labour (socialist) government to a private company intruding on the state's virtual monopoly over transport.

In November 1971, a new Conservative (centre right) government changed tack again and announced that MacBrayne's subsidy for serving Islay was to be withdrawn from March 1972. Instead, WF would be subsidised to extend their operations to Colonsay. Jura would now be served solely by WF's small vehicle ferry across the Sound of Islay from Port Askaig to Feolin which had begun in 1969: separate arrangements would be made for Gigha.

What the government hadn't reckoned on, though, was the strength of local opposition to this move, particularly from Port Ellen which would be left without a ferry as WF would be sailing only to Port Askaig. After much debate, the government changed tack again and WTP was reprieved once more. In early 1973 - by which time, incidentally, MacBrayne's and the CSP had merged to form Caledonian MacBrayne (Calmac) - the Arran was converted to ro-ro and from April that year commenced sailing from WTP thrice daily but only to Port Ellen. Colonsay had been served from Oban since the beginning of 1973 as it still is to this day.

(Here I have to admit I'm not sure how Gigha was served in 1973 and early 1974 because calls there - once a day, three days a week - en route to Port Ellen don't appear in Calmac timetables again till summer 1974.)

It was in connection with the Arran commencing service as a stern loading ro-ro ferry in April 1973 that WTP was extended by the addition of the leg out into the loch perpendicular to the coast as seen in the Google Earth image below:-

The Arran now berthed along this new leg, bow-out, and lowered her stern ramp onto the old pier which had been modified by the addition of a concrete ramp being let into it: the tidal range in West Loch Tarbert is small so expensive adjustable shore ramp (linkspan) was not necessary and this is principally why WTP survived into the car ferry era. The Google Earth image shows how shallow the loch is at WTP and how little room for manouevre there is: before the leg was built, the ships had to be warped round with ropes (a sort of maritime equivalent of a three point turn) to point them outward for the return journey to Islay.

The Arran now berthed along this new leg, bow-out, and lowered her stern ramp onto the old pier which had been modified by the addition of a concrete ramp being let into it: the tidal range in West Loch Tarbert is small so expensive adjustable shore ramp (linkspan) was not necessary and this is principally why WTP survived into the car ferry era. The Google Earth image shows how shallow the loch is at WTP and how little room for manouevre there is: before the leg was built, the ships had to be warped round with ropes (a sort of maritime equivalent of a three point turn) to point them outward for the return journey to Islay.In August 1974, Calmac took delivery of a new and faster ship to operate the Islay services. Named Pioneer in memory of the paddle steamer which had served Islay from 1905 to 1940, she was deliberately designed with a shallow draught to be able to operate from WTP.

As the 1970s progressed, it became clear there wasn't enough trade to support the sailings of both WF's and Calmac's ferries. Inevitably it was the smaller private company which suffered: in August 1976, they were forced to sell the Sound of Jura, the larger ship (pictured above) they had ordered in 1969 in the first flush of success, and revert to using their smaller original ship, the Sound of Islay. Then, in what could be viewed as a predatory move, Calmac bought WF's pier down the loch at Kennacraig in late 1977. The Pioneer gave the last sailing to Islay from WTP on 25 June 1978, thus closing more than 150 years of history.

The picture below (from John Newth's collection and used here with his kind permission) shows WF's Sound of Islay (left) and Calmac's Pioneer (right) together at Kennacraig. The expression "cuckoo in the nest" comes to mind:-

The deeper waters and greater room to manouevre at Kennacraig allowed Calmac at last to deploy to Islay the larger ship that had been ordered away back in 1968 in connection with the still-born Escart Bay scheme - the MV Iona - from February 1979. WF eventually gave up their Islay service in September 1981 whereupon Calmac resumed sailing to Port Askaig as well as Port Ellen - it was a saga of a private operator being slowly strangled to death by a state monopoly which just couldn't happen nowadays. (Comparisons of Laker against British Airways in the 1970s come to mind as well.)

West Tarbert Pier survived the departure of scheduled sailings to Islay in 1978 to become a busy fishing pier today run by Argyll and Bute Council. I'll conclude with some recent photographs by, respectively, Kevin McGroarty, "hebrides" and John Newth and all used here with their kind permission:-

Finally, I should record my own memory of WTP, the last time I was there. Easter 1975, when I was 11. It was the first time I ever boarded a Calmac ferry, the 06.30 departure of the Pioneer to Port Ellen. We'd stayed on the pier in our caravan overnight - great fun when you're 11 and a budding ferry enthusiast! This is your correspondent later that day.

Finally, I should record my own memory of WTP, the last time I was there. Easter 1975, when I was 11. It was the first time I ever boarded a Calmac ferry, the 06.30 departure of the Pioneer to Port Ellen. We'd stayed on the pier in our caravan overnight - great fun when you're 11 and a budding ferry enthusiast! This is your correspondent later that day.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

West Tarbert Pier - Part 1

But until 1978, they sailed from a pier three miles further up the loch, almost at its head, called West Tarbert Pier (WTP).

But until 1978, they sailed from a pier three miles further up the loch, almost at its head, called West Tarbert Pier (WTP).

The picture above shows WTP approaching from East Tarbert. It also shows how the main road from Tarbert to Campbeltown - the A83 now - used to run along the shore past the pier. Later (I'm not sure when but 1940s-50s I think), the road was re-routed inland (as shown on the map above) with the old road remaining as a dead end at WTP.

The picture above shows WTP approaching from East Tarbert. It also shows how the main road from Tarbert to Campbeltown - the A83 now - used to run along the shore past the pier. Later (I'm not sure when but 1940s-50s I think), the road was re-routed inland (as shown on the map above) with the old road remaining as a dead end at WTP. The earliest timetable for the Islay service I have is for 1884. It shows the steamer left Glasgow at 7.00am and reached East Tarbert at 11.45am. Coaches were on hand to convey passengers and their luggage to WTP for the Islay steamer. This left at 12.40pm and arrived at Port Ellen (Port Askaig on Fridays) on Islay at 3.40pm via a call at Gigha. 8 hours 40 minutes from Glasgow to Islay - not bad going for 1884. Today, the same journey (by Citylink coach from Glasgow to Kennacraig as the steamer service to East Tarbert was discontinued in 1970) takes about 6 hours 30 minutes.

The earliest timetable for the Islay service I have is for 1884. It shows the steamer left Glasgow at 7.00am and reached East Tarbert at 11.45am. Coaches were on hand to convey passengers and their luggage to WTP for the Islay steamer. This left at 12.40pm and arrived at Port Ellen (Port Askaig on Fridays) on Islay at 3.40pm via a call at Gigha. 8 hours 40 minutes from Glasgow to Islay - not bad going for 1884. Today, the same journey (by Citylink coach from Glasgow to Kennacraig as the steamer service to East Tarbert was discontinued in 1970) takes about 6 hours 30 minutes.  Either option would likely have spelt the end for WTP as, even if upgrading the existing services had been adopted rather than the Overland Route, a new generation of car ferry would have required a new terminal because the head of West Loch Tarbert is shallow around WTP as can be seen below.

Either option would likely have spelt the end for WTP as, even if upgrading the existing services had been adopted rather than the Overland Route, a new generation of car ferry would have required a new terminal because the head of West Loch Tarbert is shallow around WTP as can be seen below. In February 1968, the Government rejected the Overland Route on grounds of cost. As well as new ferries, it would have involved upgrading more than 30 miles (50km) of single track roads to Keills and on Jura at an overall cost of £3.2m. Instead, the Government preferred to spend £1.1m on a new ro-ro car ferry to operate from a new pier at Escart Bay, about a mile down the loch from WTP. This would serve Port Askaig, Colonsay and Port Ellen. Jura would be served by a new ferry across the Sound of Islay to Feolin instead of the traditional call at Craighouse en route to Port Askaig and Gigha would have its own independent ferry. This option could also be delivered much more quickly than the Overland Route and within the predicted remaining life of the Lochiel.

In February 1968, the Government rejected the Overland Route on grounds of cost. As well as new ferries, it would have involved upgrading more than 30 miles (50km) of single track roads to Keills and on Jura at an overall cost of £3.2m. Instead, the Government preferred to spend £1.1m on a new ro-ro car ferry to operate from a new pier at Escart Bay, about a mile down the loch from WTP. This would serve Port Askaig, Colonsay and Port Ellen. Jura would be served by a new ferry across the Sound of Islay to Feolin instead of the traditional call at Craighouse en route to Port Askaig and Gigha would have its own independent ferry. This option could also be delivered much more quickly than the Overland Route and within the predicted remaining life of the Lochiel.Friday, October 23, 2009

Stromeferry

|

| Photo credit Marc Heckert |

But what most people don't realise, as they sweep past in their motor cars pondering on the enigmatic sign, is that not only was there once a ferry but that there was also once a railway terminus at Stromeferry.

Let's clear one thing up first: "Stromeferry" (one word) is the name of a village which still exists. "Strome Ferry" (two words) was the name of a car ferry crossing over the narrows of Loch Carron from said village which ceased to exist in 1970. So to those who say that an entire generation has grown up since the ferry was discontinued and don't need to be told it no longer exists, I would agree. It was always totally illogical to put up a sign to something which no longer existed. Any new sign should point simply to the village of Stromeferry (one word).

In subsequent posts, I'll tell you about the railway terminus and the car ferry, neither of which exist any longer, at Stromeferry, down through the trees by the shore of Loch Carron, left at the enigmatic sign ...

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Ardverikie

The 1941 novel centres on a fictional clan chieftain, Donald MacDonald of Ben Nevis, whose seat is Glenbogle Castle. A comedy of manners on Highland aristocracy before the War, the title is a spoof on Sir Edwin Landseer's famous 1851 painting of a stag called "Monarch of the Glen".

Landseer's most famous work is the lions at the foot of Nelson's Column in London.

I haven't read MOTG. I started reading it when the BBC series came out but got bored after a few pages ... unlike Whisky Galore which I've read umpteen times and enjoy more with each successive read. I must try MOTG again. In fact, I will as soon as I've finished "A Summer in Skye" by Alexander Smith in 1865 which I'm currently reading (again - more of that anon).

When the BBC picked up MOTG, about all they kept from the novel was the name Glenbogle. Donald MacDonald became Hector MacDonald (played by Richard Briers - most famous for classic early 70s sitcom "The Good Life"). They also kept neighbouring laird Hugh Cameron, referred to as Kilwhillie after the habit - so accurately observed by Compton MacKenzie - Highland lairds had of referring to themselves by the name of their ancestral estate.

The location for Glenbogle in the BBC series was a house called Ardverikie on the south side of Loch Laggan on the A86 between Newtonmore and Spean Bridge.

The location for Glenbogle in the BBC series was a house called Ardverikie on the south side of Loch Laggan on the A86 between Newtonmore and Spean Bridge.

Pronounced "Ard-VER-icky", it's not far from where MacKenzie imagined the fictitious Glenbogle, the only clue to the location of which given in the book is that it's two hours walk from (fictitious) Loch na Craosnaich which is five miles from the road from Fort William to Fort Augustus (the A82).

Ardverikie was built in the 1870s by Sir John Ramsden Bt., a rich Yorkshireman whose fortune derived from the fact that he happened to own the land Huddersfield was built on. Ramsden rented the shooting rights over a large portion of the estates of Clan MacPherson of Cluny on the understanding that Cluny would pay compensation for improvements (lodges, gamekeepers' cottages etc.) at the termination of the lease. When the impoverished Cluny couldn't pay, Ramsden accepted the land in lieu (and you have to wonder if that wasn't the plan all along ...)

Ardverikie remains in Ramsden's family to this day although, having passed through some female heiresses along the way, the present owner rejoices under the splendidly upper-crust name of Patrick Gordon-Duff-Pennington. The surrounding estate extends to 38,000 acres (15,000 hectares)

Ardverikie remains in Ramsden's family to this day although, having passed through some female heiresses along the way, the present owner rejoices under the splendidly upper-crust name of Patrick Gordon-Duff-Pennington. The surrounding estate extends to 38,000 acres (15,000 hectares)

This is how Ardverikie is described in the pompous prose of the Highlands & Islands volume of Pevsner:-

a relentlessly asymmetrical display of canted bays, broad-eaved gables, round and octagonal towers with machicolations under their witch's-cap slate roofs, and even a turret corbelled out from a squinch arch. The effect, despite the corbelling, transomed windows, Tudorish hoodmoulds and occasional crosslet arrowslits, is more cottage orne than Baronial. Or would be, were it not for the tower which rises above it all. This is Baronial with a vengeance ...

Judge for yourself:-

My judgement is that Ardverikie is the most extreme - dare I say exuberant, audacious - example of a rich Victorian Englishman's fantasy in the Scottish Highlands bar none except possibly Balmoral. It's remarkable that the present generation of the family still has the money to keep this pile in good condition - the BBC filming MOTG on location here will have helped. It deserves to be kept, I think.

My judgement is that Ardverikie is the most extreme - dare I say exuberant, audacious - example of a rich Victorian Englishman's fantasy in the Scottish Highlands bar none except possibly Balmoral. It's remarkable that the present generation of the family still has the money to keep this pile in good condition - the BBC filming MOTG on location here will have helped. It deserves to be kept, I think.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Whisky Galore

Many are aware that Whisky Galore is based on the true story of a ship loaded with whisky being wrecked on a Hebridean island during the Second World War and how the islanders set about "salvaging" large quantities of their favourite tipple which, of course, was severely rationed due to the war. But the aspect of the story that's always interested me the most is how the ship, the SS Politician, came to be wrecked.

1941. To fund the war effort, Britain needs to export goods to the USA. It was horrendously dangerous for the ships and crews of the Merchant Navy as German U-Boats were waiting just off the British coast to pick off merchant ships almost as soon as they had left port. In the year between July 1940 and June 1941, 3.5 million tons of British ships were sunk - the equivalent of almost 450 ships the size of the Politician.

Two tactics were adopted to attempt to protect the shipping - convoys escorted by Royal Navy warships (safety in numbers) and individual merchant ships making a dash for it in the hope of avoiding the U-boats concentrating on richer pickings amongst the convoys.

Belonging to the firm of T & J Harrison, the 18 year old Tees-side built Politician (8,000 tons, 450 feet/140m) left Liverpool on 3 February 1941 on the latter type of mission under the command of the impressively named Captain Beaconsfield Worthington. She was not loaded solely with whisky but carried 22,000 cases of it amongst a mixed cargo of literally everything from motor cycle hubs to machetes.

Bound for Jamaica and New Orleans, she planned to outwit the U-Boats by not sailing due west round the north of Ireland but instead sailing north inside the Outer Hebrides before turning west. Departing Liverpool at 9.00am, the Politician sailed north through the Irish Sea then the North Channel between the Mull of Kintyre and Ireland.

Around midnight she was between the Rhinns of Islay and Malin Head where she altered course to starboard to aim for a position 10 miles west of the Skerryvore Lighthouse.

Sighting the Skerryvore light was not recorded in the ship's log but at 4.08am on the morning of 4th February - when she must have been around 10 miles west of it - the Politician altered course to starboard again onto a heading of 013 degrees (True) to take her between Skye and the Outer Hebrides. The weather at the time was a south-westerly gale, rough sea, overcast and raining.

Three and a half hours later, at 7.40am, the bridge was alerted by a call of "Land Ho" from the look-out. But they were appalled to hear that the land sighted was off the starboard (right) bow instead of to port (left) as might have been expected given the intended course. The officer on watch, the mate, Mr Swain, frantically ordered the helm to be put hard to port and the engines full astern (must have been not unlike when the Titanic sighted the iceberg off its starboard bow) but the Politician almost immediately ran aground. The engines were kept running astern for 20 minutes but it was no good and eventually they were shut down as the engine room flooded.

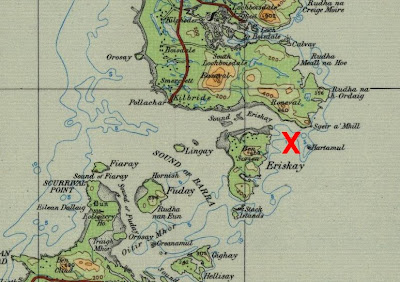

I'm not sure exactly where the Politician grounded but it was somewhere in the shallows at the east end of the Sound of Eriskay.

How could this navigational blunder have happened? My own amateur calculations with the aid of Google Earth show that a course of 013 degrees (True) would have taken the Politician inside the Outer Hebrides if she had indeed altered course 10 miles west of the Skerryvore. But if she had altered course only 3 miles out, 13 miles west of the lighthouse - easily done in the age before radar and GPS - then 013T would take her to where she foundered.

The land off the starboard bow sighted by the look-out was the south-east point of South Uist, Ru Melvick (where Sgeir a' Mhill is marked on the map above) but Captain Worthington had no idea where the Politician was. A distress call at 8.22am, 40 minutes after the grounding, reported "Ashore south of Barra Island, pounding heavily." In fact, she was ten miles away, north of Barra: a Royal Navy vessel sent to assist, HMS Abelia, went off on a wild goose chase south of Barra as did the Castlebay lifeboat which was launched at 10.00am.

Although she had grounded in shallow water and was in no danger of sinking, Captain Worthington was concerned that the Politician might break up in the heavy seas. So at 10.30am 26 non-essential crew members (cooks etc.) were lowered in a lifeboat. The boat was swept north before the storm and wrecked on the shore of South Uist but miraculously they all managed to scramble ashore. This was witnessed by islanders on Eriskay who put a sailing boat out and, with incredible navigational skill, managed to rescue the stranded crewmen to safety.

Above - the Sound of Eriskay looking north to South Uist. The point where the lifeboat was wrecked is just out of view to the right while the wreck of the Politician itself is about a mile to the right of this view.

By mid afternoon, the weather had begun to moderate so the Eriskay folk decided to take the rescued sailors back out to the Politician. Thus, at 3.00pm, more than 7 hours after the grounding, did the officers finally learn their true position. The Castlebay lifeboat was diverted and arrived alongside at 4.45pm to evacuate all the crew to Barra.

Thus concluded the immediate emergency of the grounding. The aftermath was that salvage of the cargo began a fortnight later on 18 February and was completed on 12 March. Significantly for posterity, the salvors did not consider the whisky on board worth saving - spirits with no tax paid on them (because they'd been intended for export) had insufficient value to warrant the effort.

It was in the interim before the salvaging of the ship itself began in May that the looting - or "rescuing" depending on your viewpoint - of the whisky aboard the wreck of the Politician by the local islanders took place. It's estimated that around 2,000 cases of whisky were clandestinely removed. The gangs of navvies building the RAF aerodrome on Benbecula would have provided a ready market. 30 people were convicted of theft at Lochmaddy Sheriff Court, receiving sentences ranging from fines of £2 to 2 months in prison. A significant feature in the prosecution cases was being found in possession of oil stained clothes indicating that the wearer must have been in the holds of the Politician where its fuel oil was still swilling around from ruptured tanks - nowadays there would be more concern about the environmental damage than the unpaid duty. Taking account of the fact that the local customs officer's car was also torched in its garage, it was not all the "jolly jape" portrayed by Whisky Galore.

As for the Politician herself, she was briefly refloated on 22 September to be temporarily moved to a nearby sand bank but by bad luck she settled on a rock which broke her back dashing all chances of saving the ship as a whole. Instead, in spring/summer 1942, she was cut in half and the forward section towed away in August. The aft section was cut down to low tide level and the remainder dynamited to prevent any chance of any remaining whisky on board - thought to be around 3,000 cases - falling into the wrong hands.

As for the Politician herself, she was briefly refloated on 22 September to be temporarily moved to a nearby sand bank but by bad luck she settled on a rock which broke her back dashing all chances of saving the ship as a whole. Instead, in spring/summer 1942, she was cut in half and the forward section towed away in August. The aft section was cut down to low tide level and the remainder dynamited to prevent any chance of any remaining whisky on board - thought to be around 3,000 cases - falling into the wrong hands.

There are many other aspects of the "Whisky Galore" saga that could be mentioned (e.g. the Jamaican banknotes in the Politician's cargo) but I'll leave it by saying that Captain Worthington and Mr Swain, the mate, were both cleared of any responsibility for the wreck of the Politician and both survived the War. Swain went on to command another Harrison Lines ship and Worthington survived another sinking in 1942 to die in his bed in 1961 aged 84.

All the factual info in this post is drawn from the book "Polly" by Roger Hutchinson, 1990 reprinted 1998. I don't know if it's still in print or not.

And finally, if you've never read the novel "Whisky Galore", then you should. Compton MacKenzie knew islands well and captured their essence perfectly but without patronising the islanders (as for example the BBC patronised Highlanders in its version of Monarch of the Glen). The film was shot on location in Barra in 1948. I first saw it in the village hall at Achiltibuie in the early 70s but I prefer the book. The last time I was reading it, I was on a Calmac ferry in the Sound of Barra which ran aground on a sand bank, albeit very briefly before moving off unharmed! No whisky or Jamaican bank notes were aboard as far as I know!

And finally, if you've never read the novel "Whisky Galore", then you should. Compton MacKenzie knew islands well and captured their essence perfectly but without patronising the islanders (as for example the BBC patronised Highlanders in its version of Monarch of the Glen). The film was shot on location in Barra in 1948. I first saw it in the village hall at Achiltibuie in the early 70s but I prefer the book. The last time I was reading it, I was on a Calmac ferry in the Sound of Barra which ran aground on a sand bank, albeit very briefly before moving off unharmed! No whisky or Jamaican bank notes were aboard as far as I know!