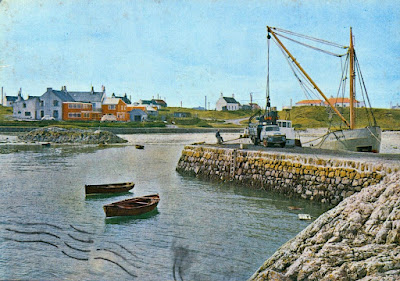

The photo above captures a moment in transport history: the type of ship of which the one in the background is a pioneer (a car ferry) is going to put the type of ship in the foreground (a puffer) out of business. The puffer is meeting its nemesis for the first time: 30 years later, the cargo it carries will all be going in lorries carried on the ferries.

The ferry is MacBrayne’s Clansman, one of three sister ships introduced in 1964 which were the first car ferries to operate on the west coast of Scotland outside the Firth of Clyde. The puffer unloading coal, which she would have brought from a port on the Clyde like Troon or Ardrossan, is the Spartan which belonged to a company called Hay Hamilton, one of the ‘big two’ puffer operators at the time. She was built in 1942 and remained in service until 1980.

The photo got me looking in to the history of the puffer fleets and which of them were the last survivors and the following is a write up of my findings. It’s by no means original research and most of my information comes from two sources: Len Paterson’s book The Light in the Glens – The Rise and Fall of the Puffer Trade pictured below. This is a must read for anyone interested in the subject and you can read it free online at Archive.org here. (You have to create an account but it’s free.) And my second source is the excellent ‘Puffers and VICs’ (I’ll explain what a VIC is presently) website by Alastair MacKenzie. It contains a potted history (so far as known) of about 350 puffers (out of around 400 built). Sadly, the site no longer being kept up but you can see the archive here.

Also essential reading is Keith McGinn's Last of the Puffermen describing life as crew on the puffers in the 1960s and 70s: it's also on Archive.org here.

So this is what I distilled out of these sources: the puffer was born on the Forth & Clyde Canal in the 1850s basically by the addition of a steam engine to a barge (which tended to be called a ‘scow’ or ‘lighter’) so it could propel itself rather than be towed by a horse. The first ever steam lighter (for some reason one never refers to ‘steam scows’) was the Thomas, a lighter to which a steam engine was added in 1856. If that seems rather late in the history of steam propulsion considering the first commercial seagoing steamship, the Comet, commenced service in 1812, it's because paddle steamers like the Comet had been experimented with on the canal but found impractical, not least because the paddle boxes on either side of the vessel's hull took up too much space in the locks. The breakthrough of the 1850s which made steam practical on canals was propulsion by screw (propeller). The first purpose built steam lighter was the Glasgow in 1857. She and the Thomas could carry about 80 tons of cargo (or in nautical parlance, they had a 'deadweight' (DWT) of 80 tons) and so successful were they due to the economies involved in needing only two boatmen as opposed to two boatmen plus a horse and a horseman that there were about 25 steam lighters by 1860 and 70 by 1870.

|

| A very heavily laden puffer on the canal |

|

| The sailing gabbart Anna Bhan at Tobermory in the 1930s |

To deal with waters not always as flat as those encountered on a canal, sea-going puffers also had to be equipped with protections such as coamings and hatch-covers. Three types developed: the ‘inside boats’ operated primarily on the canal but might occasionally stick their noses out into the firths; ‘shorehead boats’ operated primarily at sea, only occasionally going into the canal, but never venturing beyond Garroch Head; and the ‘outside boats’. Even more strongly equipped, and with the design tweaked to increase the deadweight (DWT - load carried) to about 120 tons, these could operate in the outer Firth of Clyde, cross to Ireland or transit the Crinan Canal to the north west coast and islands. But all three shared the same dimensions of 66 feet long by 18 feet wide so they could fit in the locks of the Forth & Clyde Canal and giving puffers' hulls their characteristically ‘boxy’ shape: even an outside boat had to fit the locks because, as we shall see, most puffers were built on the canal, even if they planned seldom to return to it.

|

| Screengrab from the title sequence of the 1974 series: full episode here |

For many people, their mental image of a puffer is of the Vital Spark in the various television incarnations between 1959 and 1995 of Neil Munro’s Para Handy tales. The distinctive feature of the puffer as seen there (to me, anyway) was the wheelhouse behind the funnel. But puffers, even outside boats like the Vital Spark, only began to be equipped with wheelhouses during the Second World War. The Para Handy stories were written 1905-23 when the helmsman would have stood in the open. So the profile of the Vital Spark would actually have been more like this:-

|

| The puffer Salmon in the Kyles of Bute. Built in the 1870s, she was based at Oban from about 1902 until the late 1930s. Picture and info by kind permission of Graham Lappin |

There's some footage of a puffer, the Saxon, unloading coal at the pier at Millport here (fast forward to 17:20) but the beauty of the puffer was that, with its relatively flat bottom, it could serve remote island or mainland communities without a pier: if the Vital Spark is one enduring image of a puffer, the other is one beached and unloading to a horse and cart at low tide.

|

| A beached puffer unloading to a horse and cart at Sanna in Ardnamurchan. Picture credit: Jon Haylet |

|

| The Briton being launched sideways into the canal at J & J Hay's yard at Kirkintilloch in 1905. Picture by kind permission of Graham Lappin |

|

| Hay's yard was to the left of the bridge. Follow this link for a high res version of that pic you can zoom in on and see a vessel under construction in the yard. Another aerial pic here. |

To begin with, Hays' puffers' names were usually first names beginning with A (e.g. Agnes, Albert, Alfred, Alice, Amy, Arthur) but from the 1890s they adopted the theme of races or tribes: we've already met the Spartan, Saxon and Chindit in this series and there were many more including the Kaffir pictured below heavily laden in the Crinan Canal at Ardrishaig:-

Ross & Marshall of Greenock was formed in 1872 by the amalgamation of the businesses of Alexander Ross, a coal merchant as well as puffer operator, and James Marshall who owned the Clyde Stevedoring Company. They also built some of their own ships and all were named ending in '-light' (e.g. Raylight, Skylight, Starlight etc.) or less commonly '-lite' (e.g. Mellite).

Ross & Marshall tended to concentrate more on the trade beyond the

Firth of Clyde. In this regard, the locks on the Crinan Canal were 88

feet long compared with the Forth & Clyde's 66 feet so R&M were

early exponents of a longer 'Crinamax' class of puffer with a DWT of

180 tons such as the Warlight (I) pictured below.

|

| Warlight (I) in the Sound of Mull. The red, white and black funnel was Ross & Marshall's house colours. Picture credit: Andy Carter |

Hamilton & MacPhail was formed in 1948 by the merger of G & G Hamilton of Brodick in Arran and the business of Colin MacPhail. The Hamilton family had been in the costal shipping business since 1828 when the second and third generations, Adam and his sons, George and Gavin, moved into steam navigation in 1895 with their self built puffer, the wooden Glencloy (I). Their subsequent ships all had Arran themed names. Colin MacPhail had been in business since 1903 with vessels named after Loch Fyne glens. The merged fleet consisted of Rivercloy, Invercloy (II), Glencloy (III) and Glenrosa (I) from Hamiltons and Gleannshira and Glenaray from MacPhails.

|

| G & G Hamilton's Glencloy, third of that name in their fleet, is seen here at Brodick. She was an 85' 'Crinamax' puffer built in 1930 which served until scrapped in 1967 |

Now we need to talk about VICs. It stands for 'Victualling Inshore Craft' and was a class of vessel commissioned by the Ministry of War Transport (MoWT) during WW2 to tender to Royal Navy ships at dockyards in Britain and throughout the Empire (e.g. Malta and Hong Kong). 63 VICs were built to J & J Hay's design for a 66 foot puffer and a further 39 80 foot VICs were also built (though I'm not sure who's design the latter were). All, of both classes, were built in England except for one 66 footer built by Hays at Kirkintilloch. And all, of both classes, were named simply VIC plus a numeral (eg. VIC1, VIC2, etc. up to VIC106: four numbers - 13, 58, 100 and 104 were not allocated).

After the war, many VICs were declared surplus (though many remained with the Navy too, the last one - VIC65 - surviving until 1979). Nineteen were acquired by the puffer operators to replace their older tonnage: J & J Hay bought three 66 footers (VIC11 renamed Zulu, VIC18 (Spartan: this was the one they built) and VIC87 (Dane)) and two 80 footers (VIC64 (Celt) and VIC82 (Sir James the only vessel in the Hay fleet in the 20th century not to have a 'race/tribe' name). Ross & Marshall bought two 66 footers (VIC23 renamed Limelight and VIC26 (Polarlight)). G&G Hamilton acquired 66 footer VIC29 renamed Glenrosa and Colin MacPhail acquired VIC89 renamed Glenaray (there's a few seconds of footage of her here at 01:17) Eight more 66 foot VICs and two other 80 footers were acquired by private operators.

.jpg) |

| Hamilton & MacPhail's Glenrosa ex VIC29 in the Crinan Canal at Bellanoch Bridge |

Although the smallest of the 'big three' puffer companies at their formation in 1948, Hamilton & MacPhail were the most forward thinking. An experiment with diesel engined puffers had been made in the 1910s (six vessels built at Hays with names Innis- (e.g. Innisgara) for the Coasting Motor Shipping Co. Ltd) but they hadn't been a success: motor vessels' time hadn't quite come for coasters then but it had by the 1950s. H&M broke new ground in 1953 by commissioning the first newbuild diesel engined puffer since the failed experiment. She was the 84 foot 'Crinamax' Glenshira built at Scotts of Bowling.

| |

| The Glenshira at Bellanoch Bridge on the Crinan Canal. The puffer in the background appears to be independent operator Alexander McNeil's Logan. Picture credit Robert Sinclair | |

A diesel engine and its fuel tank took up far less space than a 12 foot boiler with its chimney on top plus the engine itself and bunkers for 10 tons of coal to fuel it. So the wheelhouse could be moved forward to where the top of the boiler and the chimney had been and the exhaust pipe from the engine, encased in a largely decorative funnel, could be moved aft of the wheelhouse. A lot of space was freed up aft for much improved crew accommodation (which had hitherto been in the fo'c'sle) and the Glenshira had a DWT (carrying capacity) of 190 tons compared with the 180 of a steam 80-85 foot ‘Crinamax’.

|

| The Glenshira unloading coal at Scarinish on Tiree. |

The second diesel puffer was the Pibroch (II) built at Scotts of Bowling for Scottish Malt Distillers Ltd in 1957. A very similar vessel to the Glenshira, she replaced the Pibroch (I), a traditional 66 foot steam puffer built in 1923 which SMD used to take grain to, and barrels of whisky from, their distilleries on Islay.

|

| The Pibroch (II) in the Clyde. Photo credit: BOBBY |

Also in 1957, Ross & Marshall had planned their new ‘Crinamax’ Stormlight (III) to be diesel powered but they got cold feet at the last minute when political instability in Iran caused an oil shock so she was completed with steam power. For all its faults, at least coal was produced at home in Britain which oil wasn't at that time. This made the Stormlight the last steam powered puffer to be built but she was subsequently converted to diesel in the late 1960s .

In 1958, Hamilton & MacPhail achieved another first by being the

first firm to commission a ship for the West Highland trade too big to

fit the Crinan Canal locks. This was the 110 foot Glenshiel with a DWT of 240 tons.

|

| The Glenshiel loading coal at Troon. Picture credit BOBBY |

Lagging behind their competitors somewhat, it wasn't until 1959 that J & J Hay commissioned their first motor vessel, the 240 ton DWT Druid (III) pictured below:

|

| The Druid (III) off Wemyss Bay. Photo credit: Ballast Trust |

At the same time as ordering the Druid, Hays began a programme of converting to diesel their four newest steamers, the 66 footers Lascar, Anzac, Kaffir and Spartan (ex VIC18). As with the new motor vessels, the space freed up by the removal of boiler and chimney was reallocated to improved crew accommodation (the four portholes in the pictures below) and the wheelhouse could be brought forward with the exhaust pipe from the engine going up behind it.

|

| A puffer in the motor era: the Spartan, converted to diesel in 1961, discharging to trailers hauled by tractors on the beach at Iona |

At this point, I have to introduce a self imposed terminological point: try as hard as I might, I can't think of a ship too big to use the Crinan Canal, or one of any size built as a motor vessel, as a 'puffer'. So from hereon, I'm going to call these 'coasters' and I reserve the term 'puffer' (or 'canal boat') for ships built as steamers and that could fit the canal, including after they'd been converted to diesel.

|

| Two motorised puffers, Anzac and Lascar, at Scarinish, Tiree in the 1960s |

In 1962, tragedy struck J & J Hay when the Druid capsized at the mouth of the River Ribble with the loss of all her crew. Adding the fact that they were about to lose their yard at Kirkintilloch due to the impending closure of Forth & Clyde Canal at the end of that year, Hays were at a low ebb. So the merger the following year, 1963, with Hamilton & MacPhail was unsurprising. The new firm of Hay Hamilton was, in effect, a marriage between H&M's motor vessels Glenshira and Glenshiel and Hays' four motorised 66 foot puffers, Kaffir, Anzac, Lascar and Spartan. Hays' remaining steam puffers, all 66 footers - Turk, Slav (these two were shorehead boats which had never been fitted with wheelhouses), Gael, Texan, Dane (ex VIC87), Inca, Cretan and Boer - were all scrapped over the next two years as was H&M's steamer Glenaray (ex. VIC89). Two other H&M steamers - Glencloy (III) and Invercloy (II) - were reprieved until 1967 because they'd been converted to oil burning in 1948. Meanwhile, two new motor coasters had been commissioned, the almost identical 109'/240 ton DWT sisters Glenfyne (1965) and Glencloy (IV) (1966). Hay's 'race/tribe' naming theme was never revived after the loss of the Druid and this Glencloy turned out to be the last newbuild for service in the Clyde and West Highland trade.

|

| 1960s newspaper advert for Hay Hamilton. The ship is the Glenfyne or the Glencloy |

In 1963, at the same time as Hays and Hamilton & MacPhail were merging, Ross & Marshall was taken over from the Campbell family, coal merchants who had owned it since the retirement of its eponyms in 1913, by Clyde Shipping Company Ltd. A firm which could trace its origins in shipping on the Clyde back to 1815, its focus in the 1960s was on the coastal cargo trade and tug boats: it was the owner of the fleet of tugs with the 'Flying' names (e.g. Flying Spray, Flying Phantom etc.)

Under the new management, a similar process of transition

from steam puffer to larger motor coaster got underway at R&M. They commissioned the new motor vessels Raylight (II) (97'/180t) and Dawnlight (107'/240t)

in 1963 and 1965 respectively, two very similar looking boats except

for the latter being 10 feet longer. R&M also bought four second

hand vessels between 1963 and 1966 (Limelight (II), Moonlight (IV), Polarlight (III) and Warlight (II).) Meanwhile, eight steam puffers were disposed of by scrapping or sale to smaller operators over the period 1963-68 (Raylight (I), Sealight (II), Limelight (I) (ex. VIC23), Polarlight (II) (ex. VIC26), Moonlight (III), Starlight (II), Mellite and Warlight (I))

|

| Ross & Marshall's 1963 coaster Raylight (97'/180t) at Craignure in 1974. The vessel behind her is the puffer Marsa (ex. VIC85). Picture credit: Alan Reid. |

I don't know for sure which was the last steam powered puffer to trade. Even the collected wisdom of the Clyde Puffers Facebook group couldn't agree on this and I'm surprised it's not a well known maritime heritage milestone! But I think it might have been the Sitka. She had been Ross & Marshall's 66' canal boat Skylight (III) which they sold to a Troon timber merchant in 1967 and her Puffers & VICs entry tells us they converted her to diesel in 1969. Another possibility is the Stormlight (III), the one built by R&M in 1957 which had been going to have been diesel but was changed to steam at the last minute which was converted to diesel after R&M and Hay Hamilton merged (see below) which was in October 1968. If anyone has another candidate for last steamer, please do leave a comment.

|

| Glencloy (III), seen here on the beach at Iona in 1955, was one of the last steamers. Sold by Hay Hamilton in 1966 to A McNeil & Co of Greenock, they changed her name to Glenholm but scrapped her a year later. Photo credit: Barry Lewis |

Although Ross & Marshall and Hay Hamilton, had modernised and rationalised their fleets, trading conditions had become challenging in the 1960s. Penetration of better roads to more places on the mainland led to more bulk loads going by road, particularly around the Firth of Clyde. As far as the islands were concerned, road transport's hand maiden is the car ferry. These were introduced to the Clyde islands in the mid-1950s and to Mull and the Outer Hebrides in 1964 but all these ferries operated by 'hoist loading' (vehicles taken four or five at a time on a sort of 'dumb-waiter' lift from the pier down to the vehicle deck rather than driving straight on to the vehicle deck down a ramp as nowadays). This was fine for tourists' cars but less suitable for heavy lorries. So these first ferries were not yet too much of a threat to the coasters and puffers. But that began to change in 1968 with the introduction of a ro-ro (drive directly on to the vehicle deck) ferry to Islay by the private firm Western Ferries. The island's distilleries provided both outward (coal, malt, barrels) and inward (whisky) cargos which added up to about a third of the total tonnage carried by HH and R&M. In the face of these threats to their business, it made sense for them to merge and this happened in October 1968, the merged company being called Glenlight after the companies' respective vessel naming conventions. The merger also brought into the Glenlight fleet the two 66' motorised puffers belonging to Irvine Shipping and Trading in which R&M owned a 50% share, the Lady Isle (II) (ex. VIC9) and Lady Morven (ex. VIC37).

|

| The Lady Morven beached near the head of Loch Sunart in 1973. She had belonged to Irvine Shipping & Trading and became part of the Glenlight fleet in 1968. Photo credit: David Taylor |

|

| Advert in the Stornoway Gazette, April 1969 |

The ro-ro ferry to Islay took about half of GL's distillery business within a year and five years later, in 1973, about 85% of it had gone. With ro-ro ferries now being deployed to the other islands and demand for coal having declined considerably after towns like Rothesay, Dunoon, Campbeltown and Oban converted to natural gas in 1974 (gas had been provided hitherto by municipal gasworks in each town which produced gas ('town gas' or 'coal gas') by heating coal taken there by puffers), further fleet rationalisation was called for. Four vessels were disposed of between 1972 and 1974, these being Warlight (II), Polarlight (III), Glenshira (the groundbreaking first diesel 'puffer') and Lascar (pre-WW2 66' motorised puffer).

But it wasn't all bad news: road salt for gritting roads in

winter was becoming a significant cargo, its growth to an extent making up for the decline in coal (so the

coasting trade was benefiting from a crumb off the table of road transport

which was otherwise stifling it). And concrete oil rig construction at Ardyne Point opposite Rothesay between 1974 and 1978 provided a lot of work. This coupled with the prospect of more oil rig work from 1976 at Kishorn in Wester Ross where it was a planning condition that no construction material could be brought onsite by road meant that the loss of four vessels between 1973 and 1975 - Glenshiel (the 1959 first coaster too big for the Crinan Canal); Stormlight (III) (wrecked at Jura); Kaffir (66' motorised puffer wrecked at Ayr); and Raylight (II) (1963 coaster wrecked near Larne) - now placed Glenlight in the position of needing more tonnage, specifically of the larger type of ship more suited to the new trading patterns.

|

| The wreck of the Kaffir is still visible at low tide just outside Ayr Harbour. You can see her mast here. Photo credit: Bill Ryder |

In 1978, Glenlight acquired four second hand sister ships of 137 feet length and 340 tons DWT from the Thames coastal shipping firm, Eggar Forester. In accordance with the naming traditions of the two ancestor companies of Glenlight, these were renamed Glenetive, Glenrosa (II), Polarlight (IV) and Sealight (III). At the same time, the 1966 coaster Glencloy (IV) was disposed of.

|

| Glenrosa (II) and Glenetive at Greenock. Photo credit: harrisman |

In 1979, with the oil rig work now at an end, Glenlight suffered another blow by losing the seaweed trade when Alginate Industries began to send it south by lorry carried on Caledonian MacBrayne's ferries. As Calmac - which was also a road haulage firm at this time - was in receipt of state subsidy, it could afford to undercut GL's prices. This prompted a another round of debate about unfair competition in the west coast shipping industry between the state subsidised public sector and private enterprise. (The first round, ironically, was in the mid 70s when Western Ferries, operator of the pioneer ro-ro ferry to Islay which had taken the whisky trade from GL, accused the Government of trying to put them out of business by deploying a subsidised Calmac ro-ro ferry to the island.)

The Government eventually agreed to subsidise Glenlight from 1981. There were two elements to the subsidy: first, the so-called 'Tariff Rebate Scheme' whereby the Government paid a proportion of freights. So, for example, if it cost £10 to deliver a ton of coal somewhere and the TRS was 30%, the customer paid £7 and the Government paid £3. This was designed to assist the fragile economy of the West Highlands and Islands by mitigating their delivery costs while assisting GL to the extent of allowing them to set charges slightly higher than these markets might otherwise be able to bear. But TRS was hardly a licence to print money, though, because the second element of the subsidy was straight deficit funding, i.e. making up GL's losses.

But once again, it wasn't all bad news at the beginning of the 1980s. A new growth area was emerging: timber from the plantations established by the Forestry Commission after WW2 in places like Kintyre, Mull and Morvern which were beginning to mature for the first time. From a first cargo of logs loaded at Lochaline in 1980, six years later Glenlight was carrying 16,000 tons of them a year. Timber was the all important return cargo: the logs came south on a ship returning from a voyage north with coal or, increasingly as the 1980s progressed, road salt. To deal with the new timber trade, a second hand 750 ton DWT vessel renamed Glencloy (fifth of that name in the fleets of GL and its ancestor companies since 1895) was acquired in June 1986 while the two remaining 1960s 240 ton DWT coasters, the Glenfyne and the Dawnlight, were sold in 1988. The biggest customers for logs were the Caledonian Paper Mill at Irvine (the logs being landed at Troon, I assume) opened by Finnish company UPM-Kymmene in 1989 and the paper mill at Workington in Cumbria owned by Swedish firm Iggesund since 1987 (now called Holmen).

|

| Glencloy (V). Photo credit: davidpearson8 |

In 1986, the Government announced it would cease paying deficit funding from the following March. That gave Glenlight a major headache because it had been keeping its charges in the Highlands and Islands artificially low in the knowledge that the deficit funding would keep them out the red. (Its charges in other areas were at normal commercial rates and GL was making a profit there.) Protracted wrangling, consultations and reviews ensued. Deficit funding was temporarily extended but finally ended in April 1988. It was replaced by a revised Tariff Rebate Scheme in which, amongst other unhelpful changes, local authorities were no longer eligible for the discounts. As LAs were the customers for road salt, the possibility of them switching to road and ferry transport in the face of a dramatic hike in shipping costs would not only threaten about a third of GL's turnover but also have a knock on effect on its timber trade (another third of turnover) whose prices were able to be fixed at a lower level on the assumption that the ship taking the logs south had earned from a cargo of salt carried on the voyage north to collect them.

After further negotiations, the details of the TRS were tweaked a bit and GL decided to soldier on in the hope that the ballooning timber trade would be their salvation (35,000 tons were being carried in 1989, this being projected to rise to 100,000 tons by 1995 and 300,000 tons by 2000) and that the Government might eventually see sense over subsidy. Thus, when one of the Eggar Forrester quadruplets, the Polarlight (IV), was lost in the Irish Sea in February 1989, instead of accepting the enforced retrenchment, she was immediately replaced by a second hand 400 ton DWT coaster renamed Glenfyne (II).

|

| The Glenfyne (II), left, and Glencloy (V), right, at Belfast. Photo credit: Alan Geddes |

In 1992, Glenlight began to experiment with the 'tug and barge' concept for the timber trade. This involved a barge capable of carrying 600 tons of logs, built at Harland & Wolff in Belfast and appropriately named Sprucelight, which could be beached on a shore near a forest. Timber lorries could drive on to her, deposit their loads directly on board and, when full, she would be towed south by a tug belonging to Glenlight's parent company, Clyde Shipping.

|

| One of Glenlight's barges loading logs at Raasay. Picture credit: Forestry Memories |

A second barge, Pinelight, followed in 1993. The plan ultimately

was to have three barges served by one tug - one barge loading, one

discharging and one on passage being hauled by the tug. Sending timber

south by sea will always struggle to compete with dispatching it by road

because a lorry offers a door to door service from the forest direct to

the mill whereas shipping logs involves unloading them onto the pier,

reloading them onto the ship, and reloading them again at the port of

destination onto a lorry to the mill. Tug and barge was an attempt to

improve the economics by removing one of these steps (the unloading of

the logs at the pier of departure) and having one ship (the tug) do the

job of three (the barges): there's a good article in the Glasgow Herald in 1993 about it here.

Also in 1993, GL bought the 1,200 ton DWT coaster they'd been chartering and renamed her Glenrosa (III) (The second Glenrosa, one of the Eggar Forrester quadruplets, had been sold in 1990 as had one of the others Glenetive. The last one, the Sealight (III), was wrecked in Loch Maddy in 1991.)

Meanwhile negotiations over subsidy rumbled on. The Government restored deficit funding in 1992 pending yet another review of the workings of the Tariff Rebate Scheme. But this was delayed and deficit funding wasn't renewed in 1993. Unwilling to sustain any more losses while the Government dithered, Glenlight gave notice that it would cease trading with its conventional ships (Glencloy (V), Glenfyne (II) and Glenrosa (II)) from the beginning of 1994. The two barges were retained but they too ceased operations in 1995 when the long delayed review led to the abolition of TRS. (The third barge never came to pass but the first two still exist, with their original names Sprucelight and Pinelight, albeit no longer carrying timber: the former in Devon, the latter in Greenland. I doubt their operators today realise the names encapsulate 120 years of Scottish maritime tradition and an attempt to future proof it! The Glencloy (V) was destroyed by fire in the Caribbean in 2013 but the Glenfyne (II) survives in Norway as the Kyst. The Glenrosa (II) appears no longer to exist.)

|

| Great Glen Shipping Company's CEG Universe at Lochaline |

In the the course of my brief google into the current scene, I came across the picture below: a bulk carrier devloped from a barge to which an engine and a propeller has been added and that can be beached on a Highland coast - does that sound familiar? History seems to have come full circle!

|

| Red Princess loading logs at Loch Striven. Picture credit: Troon Tugs |

In digressing off into the fate of Glenlight, I've rather lost sight of puffers (by which I mean vessels which could fit the Crinan Canal and built as steamers, even if subsequently converted to diesel). To re-cap, GL inherited six of them at formation in 1968: Anzac, Lascar, Kaffir, Spartan (ex VIC18), Lady Isle (ex VIC9) and Lady Morven (ex VIC37). As already noted, consumption of the puffer's traditional staple cargo, coal, declined by more than a half during the 1970s and GL were re-orienting their fleet towards the larger ships more appropriate to the new areas of work in that decade (oil rigs, road salt). All that said, the puffers were still suited to GL's contract servicing to the US Navy in the Holy Loch (a floating submarine dry dock with attendant tender vessel USS Holland) and deliveries of coal to remote Highland and Island locations were still a thing, albeit becoming less frequent.

|

| The Kaffir at Salen, Loch Sunart in 1973. Picture credit: David Taylor |

But although the Spartan was the last Glenlight puffer in service (or the Pibroch if you regard her as one), neither of these was the last overall. There were another five that made it into the 1970s: I've already mentioned the Sitka as candidate for the last steam puffer and she seems to have been working on the Clyde past the middle of the decade. There were also the Toward Lass (ex VIC12) and the Colonsay (II) (ex VIC84) owned by M Brown & Co. of Greenock and employed on the very unglamorous task of removing waste from the US Navy at the Holy Loch - they weren't scrapped until 1980.

Beyond the Clyde, Hugh Carmichael of Mull had the Marsa (ex VIC85) and the Eldesa (ex VIC72) mainly running timber from Craignure pier to the pulp mill at Corpach. He disposed of the Marsa in the late 70s and she never traded again after that [EDIT - see the comment below from Alistair Bennett re the Marsa] but he retained the Eldesa until he retired in 1983 (I remember seeing the Eldesa often when I used to going sailing out of Oban in the mid/late 70s.) She was sold to Easdale Island Shipping Line Ltd. They changed her name to Eilean Eisdeal and traded with her "taking bagged coal around the islands and lifting roadstone and aggregate from Bonawe [quarry], with of course a subsidy", according to someone who sounds like he knows what he's talking about here. EISL ceased trading in 1994, shortly after Glenlight did, when the Government withdrew the Tariff Rebate Subsidy so I think it's the Eilean Eisdeal which claims the crown of 'the last puffer.'

|

| A picture I took of the Eilean Eisdeal at Uig in 1991. At the time I don't think I realised I was looking at 'the last puffer' |

It's already happened in the course of this post but Para Handy and the Vital Spark are never far away from any discussion of puffers but which vessels were used in the various television series?

There were five TV series. The first was in 1959-60 (in black and white, of course) with Duncan Macrae as PH, John Grieve as MacPhail, the engineer, and Roddy MacMillan as Dougie, the mate, but I don't know which puffer was used. Then there were two series, also b/w, broadcast in 1965 and 1966 with Roddy MacMillan promoted to PH, John Grieve still as MacPhail and Walter Carr as Dougie. The ship used was the Saxon. As her name suggests, she started as a J & J Hay boat but they sold her to the Kerr brothers of Millport in 1926 who used her almost exclusively to take coal there. Her role as the Vital Spark explains why you can see lifebelts with that name on them in the video clip of her I linked to further up. She retired in 1967, still a steamer.

The first colour series of The Vital Spark was in 1973-74, same cast, and the ship used was the Sitka (ex. Skylight). And the last series was in 1994-95 with Gregor Fisher as PH and Rikki Fulton as MacPhail. The ship used was one I haven't mentioned so far, the Auld Reekie (ex VIC27). She was acquired from the Admiralty in 1966 having been working at Rosyth but only traded in civilian life for a couple of years before being purchased in 1968 by Sir James Miller, the Edinburgh house building magnate. He converted her into a youth training vessel sailing out of Oban before selling her again in 1978 (I can also remember seeing her in the 70s.) I'm not sure what she was doing between then and appearing in Para Handy in 1994. After that she languished on the Crinan Canal deteriorating until 2008 when she was acquired by Crinan Boatyard. She is now on their slip there undergoing slow but very thorough restoration: see the website for more detail. It's worth noting that the Auld Reekie was never converted to diesel and she was still steam powered when doing her youth training cruises in the 1970s. But I didn't include her in the last steam puffer stakes because I meant the last cargo rather than passenger carrying steam puffer.

|

| The Auld Reekie at Crinan still carrying her fictional Vital Spark titles from the 1994-95 series. Picture credit: frcrossnacreevy |

There's another Vital Spark as well. This is the retired puffer lying at Inveraray since 2001. This is, in fact, the Eilean Eisdeal (ex Eldesa, ex VIC72), the last working puffer. I understand that her owner wanted to officially rename her Vital Spark but that name was already taken by another boat so he chose Vital Spark of Glasgow instead: the "of Glasgow" isn't painted on her bows and at the stern it looks like her port of registry.

|

| The Vital Spark of Glasgow (ex Eilean Eisdeal, ex Eldesa, ex VIC72) at Inveraray. Picture credit: Anne Young |

|

| The VIC32 and the Rothesay ferry - such coal as is consumed there nowadays goes on the latter. Picture credit: ArgyllFoto |

Well, this post ended up being miles longer than I imagined so if anyone's read this far and has spotted any mistakes or can add any details, please leave a comment. Here are some superb galleries of images of puffers: here, here and here and I leave you with a puffer timeline:-

1856 - steam engine and propeller added to a Forth & Clyde canal lighter (scow or barge), the Thomas, for the first time: the first puffer.

1857 - first purpose built steam lighter ('puffer'), the Glasgow.

1860 - by now 20 puffers on the F&C Canal.

1867 - James and John Hay form the firm of J & J Hay (the fleet with the 'race/tribe' names e.g. Briton, Serb, Spartan etc. from the 1890s) begin building puffers at Kirkintilloch on the F&C Canal and owning operating them on the canal and then at sea.

1870 - by now 70 puffers and beginning to venture beyond the canal.

1872 - Ross & Marshall (the fleet with the '-light' names e.g. Polarlight, Dawnlight etc.) formed in Greenock.

1895 - Adam, George & Gavin Hamilton of Brodick build their first steam vessel, the Glencloy.

1903 - Neil Munro begins writing the Para Handy stories until 1923.

1905 - Colin MacPhail goes into business. His vessels are named after Loch Fyne glens.

1921 - J & J Hay become known as J Hay & sons until 1956

1941-46 - 63 'Victualling Inshore Craft' (VICs) built for the Ministry of War Transport to J & J Hay's design for a 66 foot puffer, plus a further 39 80 foot VICs, all but one in England. 19 of these were acquired after the War to serve as puffers on the west coast of Scotland.

1945 - J & J Hay build their last puffer at Kirkintilloch, the Chindit.

1948 - G & G Hamilton and Colin MacPhail merge to form Hamilton & MacPhail

1953 - first diesel puffer built by Hamilton & MacPhail, the Glenshira.

1956 - J Hay & Sons revert to being know as J & J Hay.

1957 - last steam puffer built, the Stormlight (III).

1958 - first vessel for the West Highland trade too big to use the Crinan Canal commissioned by Hamilton & MacPhail, the Glenshiel.

1959 - J & J Hay order their first diesel vessel, the Druid, and begin converting four of their puffers (Anzac, Lascar, Kaffir and Spartan) from steam to diesel.

1959-60 - first TV series of Para Handy with Duncan Macrae as PH and Roddy MacMillan as MacPhail. Don't know the puffer used.

1962 - Forth & Clyde Canal and Hays' yard at Kirkintilloch closed.

1963 - Ross & Marshall commission their first diesel vessel, the Raylight, and are taken over by Clyde Shipping Company. Hamilton & MacPhail and J & J Hay merge to form Hay Hamilton.

1965 & 66 - second and third TV series of PH. Roddy MacMillan as PH and using the Saxon.

1968 - Western Ferries introduces the first ro-ro ferry on the west coast, to Islay, threatening the puffers' and coasters' trade. Ross & Marshall and Hay Hamilton merge to form Glenlight Shipping.

1969 - last steam puffer to trade (not counting the Auld Reekie or VIC32), possibly the Sitka (ex Skylight (III)).

1974 - first colour series of Para Handy using the Sitka.

1979 - last VIC (VIC65) retired by the Admiralty and scrapped at Inverkeithing.

1980 - Glenlight's last puffer (i.e. vessel built as steamer which could fit the Crinan Canal), the Spartan, retired. First cargo of timber lifted at Lochaline.

1981 - Glenlight begin to be subsidised by Government.

1992 - Glenlight pioneer 'tug and barge' concept with timber cargos

1994 - Glenlight cease trading with their conventional fleet and last puffer in operation (not counting the VIC32), the Eilean Eisdeal (ex Eldesa, ex VIC72) retires.

1994-95 - Fifth TV series of Para Handy with Gregor Fisher as PH and using the Auld Reekie.

1995 - Glenlight cease trading with 'tug and barge' due to complete withdrawal of Government subsidy.

|

| The Roman at Brodick, early 1950s. Her name identifies her as a Hay vessel but they sold her to Alastair Kelso of Arran in 1935 and she spent the rest of her life until 1957 trading to that island. |

Great info on the coastal puffers. One very minor detail though....the Marsa continued trading for a while after she was sold by Hugh Carmichael to new Mull owners. I crewed on her till she went to Bowling for pre-survey repairs and I was paid off there. After a longer than expected spell in Bowling she worked a bit more under the new owners but I believe the work dried up. Not certain of dates but maybe 1975-76 in Bowling.

ReplyDeleteThanks for that Alistair. I've put an edit in the text next to the Marsa calling attention to your comment. Thanks again.

DeleteThanks for that Alistair. I've put an edit in the text next to the Marsa calling attention to your comment. Thanks again.

DeleteThe article may be miles longer than you expected Neil but I found every step to be pure delight.

ReplyDeleteIn addition to “Para Handy Tales” /”The Vital Spark”, and very much similar in style, I’ll point you in the direction of the 1954 Ealing comedy “The Maggie” (also known as “High and Dry”). Lots of puffer action (and inaction) around a bustling River Clyde, the Crinan Canal and Islay. The puffer was played by two vessels: the second “Boer” and “Inca”.

Thanks Roy, that's kid. I do actually have 'The Maggie' in the house, although it's a while since I've watched it, and had clocked the ID of the vessels that starred in the film although I thought that was a factoid too far in something that was getting over long! Thanks again.

DeleteLink below to a Glasgow Herald article from 2019 on the making of "The Maggie". Clicking through the six photographs in the article, did the last picture of the ship stuck on the subway inspire James Cameron to build a replica of the 'Titanic' for his movie? ;-) https://www.heraldscotland.com/life_style/arts_ents/17653648.celebrating-scotlands-forgotten-cinema-classic-maggie/

Delete