Until the BBC dramatised his 1941 novel "Monarch of Glen" for TV in the early 2000s, Sir Compton MacKenzie was more famous for his 1946 novel "Whisky Galore" and the 1949 Ealing Comedy film of the same name.

Many are aware that Whisky Galore is based on the true story of a ship loaded with whisky being wrecked on a Hebridean island during the Second World War and how the islanders set about "salvaging" large quantities of their favourite tipple which, of course, was severely rationed due to the war. But the aspect of the story that's always interested me the most is how the ship, the SS Politician, came to be wrecked.

1941. To fund the war effort, Britain needs to export goods to the USA. It was horrendously dangerous for the ships and crews of the Merchant Navy as German U-Boats were waiting just off the British coast to pick off merchant ships almost as soon as they had left port. In the year between July 1940 and June 1941, 3.5 million tons of British ships were sunk - the equivalent of almost 450 ships the size of the Politician.

Two tactics were adopted to attempt to protect the shipping - convoys escorted by Royal Navy warships (safety in numbers) and individual merchant ships making a dash for it in the hope of avoiding the U-boats concentrating on richer pickings amongst the convoys.

Belonging to the firm of T & J Harrison, the 18 year old Tees-side built Politician (8,000 tons, 450 feet/140m) left Liverpool on 3 February 1941 on the latter type of mission under the command of the impressively named Captain Beaconsfield Worthington. She was not loaded solely with whisky but carried 22,000 cases of it amongst a mixed cargo of literally everything from motor cycle hubs to machetes.

Bound for Jamaica and New Orleans, she planned to outwit the U-Boats by not sailing due west round the north of Ireland but instead sailing north inside the Outer Hebrides before turning west. Departing Liverpool at 9.00am, the Politician sailed north through the Irish Sea then the North Channel between the Mull of Kintyre and Ireland.

Around midnight she was between the Rhinns of Islay and Malin Head where she altered course to starboard to aim for a position 10 miles west of the Skerryvore Lighthouse.

Sighting the Skerryvore light was not recorded in the ship's log but at 4.08am on the morning of 4th February - when she must have been around 10 miles west of it - the Politician altered course to starboard again onto a heading of 013 degrees (True) to take her between Skye and the Outer Hebrides. The weather at the time was a south-westerly gale, rough sea, overcast and raining.

Three and a half hours later, at 7.40am, the bridge was alerted by a call of "Land Ho" from the look-out. But they were appalled to hear that the land sighted was off the starboard (right) bow instead of to port (left) as might have been expected given the intended course. The officer on watch, the mate, Mr Swain, frantically ordered the helm to be put hard to port and the engines full astern (must have been not unlike when the Titanic sighted the iceberg off its starboard bow) but the Politician almost immediately ran aground. The engines were kept running astern for 20 minutes but it was no good and eventually they were shut down as the engine room flooded.

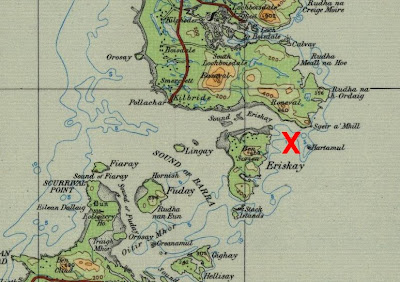

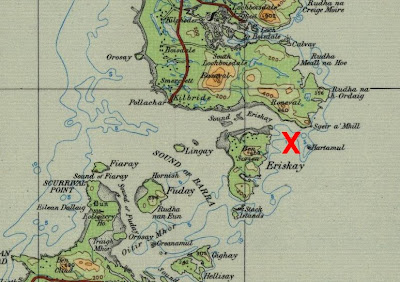

I'm not sure exactly where the Politician grounded but it was somewhere in the shallows at the east end of the Sound of Eriskay.

How could this navigational blunder have happened? My own amateur calculations with the aid of Google Earth show that a course of 013 degrees (True) would have taken the Politician inside the Outer Hebrides if she had indeed altered course 10 miles west of the Skerryvore. But if she had altered course only 3 miles out, 13 miles west of the lighthouse - easily done in the age before radar and GPS - then 013T would take her to where she foundered.

The land off the starboard bow sighted by the look-out was the south-east point of South Uist, Ru Melvick (where Sgeir a' Mhill is marked on the map above) but Captain Worthington had no idea where the Politician was. A distress call at 8.22am, 40 minutes after the grounding, reported "Ashore south of Barra Island, pounding heavily." In fact, she was ten miles away, north of Barra: a Royal Navy vessel sent to assist, HMS Abelia, went off on a wild goose chase south of Barra as did the Castlebay lifeboat which was launched at 10.00am.

Although she had grounded in shallow water and was in no danger of sinking, Captain Worthington was concerned that the Politician might break up in the heavy seas. So at 10.30am 26 non-essential crew members (cooks etc.) were lowered in a lifeboat. The boat was swept north before the storm and wrecked on the shore of South Uist but miraculously they all managed to scramble ashore. This was witnessed by islanders on Eriskay who put a sailing boat out and, with incredible navigational skill, managed to rescue the stranded crewmen to safety.

Above - the Sound of Eriskay looking north to South Uist. The point where the lifeboat was wrecked is just out of view to the right while the wreck of the Politician itself is about a mile to the right of this view.

By mid afternoon, the weather had begun to moderate so the Eriskay folk decided to take the rescued sailors back out to the Politician. Thus, at 3.00pm, more than 7 hours after the grounding, did the officers finally learn their true position. The Castlebay lifeboat was diverted and arrived alongside at 4.45pm to evacuate all the crew to Barra.

Thus concluded the immediate emergency of the grounding. The aftermath was that salvage of the cargo began a fortnight later on 18 February and was completed on 12 March. Significantly for posterity, the salvors did not consider the whisky on board worth saving - spirits with no tax paid on them (because they'd been intended for export) had insufficient value to warrant the effort.

It was in the interim before the salvaging of the ship itself began in May that the looting - or "rescuing" depending on your viewpoint - of the whisky aboard the wreck of the Politician by the local islanders took place. It's estimated that around 2,000 cases of whisky were clandestinely removed. The gangs of navvies building the RAF aerodrome on Benbecula would have provided a ready market. 30 people were convicted of theft at Lochmaddy Sheriff Court, receiving sentences ranging from fines of £2 to 2 months in prison. A significant feature in the prosecution cases was being found in possession of oil stained clothes indicating that the wearer must have been in the holds of the Politician where its fuel oil was still swilling around from ruptured tanks - nowadays there would be more concern about the environmental damage than the unpaid duty. Taking account of the fact that the local customs officer's car was also torched in its garage, it was not all the "jolly jape" portrayed by Whisky Galore.

As for the Politician herself, she was briefly refloated on 22 September to be temporarily moved to a nearby sand bank but by bad luck she settled on a rock which broke her back dashing all chances of saving the ship as a whole. Instead, in spring/summer 1942, she was cut in half and the forward section towed away in August. The aft section was cut down to low tide level and the remainder dynamited to prevent any chance of any remaining whisky on board - thought to be around 3,000 cases - falling into the wrong hands.

As for the Politician herself, she was briefly refloated on 22 September to be temporarily moved to a nearby sand bank but by bad luck she settled on a rock which broke her back dashing all chances of saving the ship as a whole. Instead, in spring/summer 1942, she was cut in half and the forward section towed away in August. The aft section was cut down to low tide level and the remainder dynamited to prevent any chance of any remaining whisky on board - thought to be around 3,000 cases - falling into the wrong hands.

There are many other aspects of the "Whisky Galore" saga that could be mentioned (e.g. the Jamaican banknotes in the Politician's cargo) but I'll leave it by saying that Captain Worthington and Mr Swain, the mate, were both cleared of any responsibility for the wreck of the Politician and both survived the War. Swain went on to command another Harrison Lines ship and Worthington survived another sinking in 1942 to die in his bed in 1961 aged 84.

All the factual info in this post is drawn from the book "Polly" by Roger Hutchinson, 1990 reprinted 1998. I don't know if it's still in print or not.

And finally, if you've never read the novel "Whisky Galore", then you should. Compton MacKenzie knew islands well and captured their essence perfectly but without patronising the islanders (as for example the BBC patronised Highlanders in its version of Monarch of the Glen). The film was shot on location in Barra in 1948. I first saw it in the village hall at Achiltibuie in the early 70s but I prefer the book. The last time I was reading it, I was on a Calmac ferry in the Sound of Barra which ran aground on a sand bank, albeit very briefly before moving off unharmed! No whisky or Jamaican bank notes were aboard as far as I know!

And finally, if you've never read the novel "Whisky Galore", then you should. Compton MacKenzie knew islands well and captured their essence perfectly but without patronising the islanders (as for example the BBC patronised Highlanders in its version of Monarch of the Glen). The film was shot on location in Barra in 1948. I first saw it in the village hall at Achiltibuie in the early 70s but I prefer the book. The last time I was reading it, I was on a Calmac ferry in the Sound of Barra which ran aground on a sand bank, albeit very briefly before moving off unharmed! No whisky or Jamaican bank notes were aboard as far as I know!

But until 1978, they sailed from a pier three miles further up the loch, almost at its head, called West Tarbert Pier (WTP).

But until 1978, they sailed from a pier three miles further up the loch, almost at its head, called West Tarbert Pier (WTP).

The picture above shows WTP approaching from East Tarbert. It also shows how the main road from Tarbert to Campbeltown - the A83 now - used to run along the shore past the pier. Later (I'm not sure when but 1940s-50s I think), the road was re-routed inland (as shown on the map above) with the old road remaining as a dead end at WTP.

The picture above shows WTP approaching from East Tarbert. It also shows how the main road from Tarbert to Campbeltown - the A83 now - used to run along the shore past the pier. Later (I'm not sure when but 1940s-50s I think), the road was re-routed inland (as shown on the map above) with the old road remaining as a dead end at WTP. The earliest timetable for the Islay service I have is for 1884. It shows the steamer left Glasgow at 7.00am and reached East Tarbert at 11.45am. Coaches were on hand to convey passengers and their luggage to WTP for the Islay steamer. This left at 12.40pm and arrived at Port Ellen (Port Askaig on Fridays) on Islay at 3.40pm via a call at Gigha. 8 hours 40 minutes from Glasgow to Islay - not bad going for 1884. Today, the same journey (by Citylink coach from Glasgow to Kennacraig as the steamer service to East Tarbert was discontinued in 1970) takes about 6 hours 30 minutes.

The earliest timetable for the Islay service I have is for 1884. It shows the steamer left Glasgow at 7.00am and reached East Tarbert at 11.45am. Coaches were on hand to convey passengers and their luggage to WTP for the Islay steamer. This left at 12.40pm and arrived at Port Ellen (Port Askaig on Fridays) on Islay at 3.40pm via a call at Gigha. 8 hours 40 minutes from Glasgow to Islay - not bad going for 1884. Today, the same journey (by Citylink coach from Glasgow to Kennacraig as the steamer service to East Tarbert was discontinued in 1970) takes about 6 hours 30 minutes.  Either option would likely have spelt the end for WTP as, even if upgrading the existing services had been adopted rather than the Overland Route, a new generation of car ferry would have required a new terminal because the head of West Loch Tarbert is shallow around WTP as can be seen below.

Either option would likely have spelt the end for WTP as, even if upgrading the existing services had been adopted rather than the Overland Route, a new generation of car ferry would have required a new terminal because the head of West Loch Tarbert is shallow around WTP as can be seen below. In February 1968, the Government rejected the Overland Route on grounds of cost. As well as new ferries, it would have involved upgrading more than 30 miles (50km) of single track roads to Keills and on Jura at an overall cost of £3.2m. Instead, the Government preferred to spend £1.1m on a new ro-ro car ferry to operate from a new pier at Escart Bay, about a mile down the loch from WTP. This would serve Port Askaig, Colonsay and Port Ellen. Jura would be served by a new ferry across the Sound of Islay to Feolin instead of the traditional call at Craighouse en route to Port Askaig and Gigha would have its own independent ferry. This option could also be delivered much more quickly than the Overland Route and within the predicted remaining life of the Lochiel.

In February 1968, the Government rejected the Overland Route on grounds of cost. As well as new ferries, it would have involved upgrading more than 30 miles (50km) of single track roads to Keills and on Jura at an overall cost of £3.2m. Instead, the Government preferred to spend £1.1m on a new ro-ro car ferry to operate from a new pier at Escart Bay, about a mile down the loch from WTP. This would serve Port Askaig, Colonsay and Port Ellen. Jura would be served by a new ferry across the Sound of Islay to Feolin instead of the traditional call at Craighouse en route to Port Askaig and Gigha would have its own independent ferry. This option could also be delivered much more quickly than the Overland Route and within the predicted remaining life of the Lochiel.