Well I did ask for suggestions but when asked for the Flying Scotsman, I have to admit my first reaction was that, while I’m interested in

railways, I’m not that interested in

locomotives and consequently don’t know much about them. And, anyway, what does the FS have to do with the west coast of Scotland? But it would have been too unutterably churlish to decline and, when I began to look into it, I found it was a more interesting subject than I’d anticipated. And there is a “Kyles link” as well.

The first thing discovered was that the Flying Scotsman was not, originally, a locomotive but the name of a rail service – specifically the London & North Eastern Railway Company’s simultaneous 10.00am departures from London King’s Cross to Edinburgh Waverley and vice versa. A locomotive built in 1923 was named Flying Scotsman after the service.

The Flying Scotsman run goes back to the 1860s but first you need to understand the structure of the British rail industry in these days. If people got frustrated after the privatisation of British Railways in the 1990s produced a couple of dozen railway companies to choose from, then pity the traveller a hundred years earlier who had a much greater number of local companies to contend with.

Three of the bigger private railway companies were the Great Northern Railway (GNR) with its headquarters at King’s Cross and main line to Leeds via Doncaster; the North Eastern Railway (NER) with its HQ at York and main line from Doncaster to Berwick-on-Tweed via Newcastle; and the North British Railway (NBR) with its headquarters at Waverley Station in Edinburgh and its main line to Berwick.

In 1862, these three “big beasts” of the Victorian railway industry formed what would now be termed a joint venture to run trains from London to Edinburgh over what would become known as the East Coast Mainline railway. The 10.00am departures were known as the Scotch Special Express. It took 10hrs 30mins to Edinburgh and included a half hour stop at York for lunch as there were no dining cars on British railways before the 20th century.

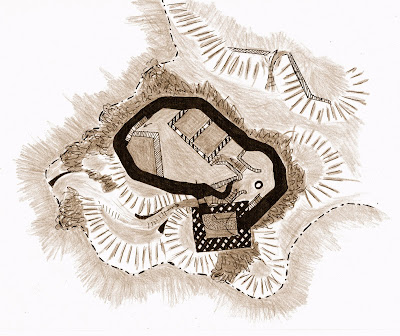

A preserved GNR Stirling class locomotive of the sort which would have hauled the Flying Scotsman in the 1870s (Picture credit Wikipedia)

The equivalent on the west coast was the Royal Scot service to Glasgow, a partnership between the London & North Western Railway (LNWR - based at Euston Station in London with lines running as far as Carlisle) and the Caledonian Railway (based at Glasgow Central Station). The Royal Scot also departed at 10.00am, running over what’s now known as the West Coast Mainline railway.

In 1923, the numerous private railway companies were all “grouped” into the so-called “Big-Four” companies. The east coast partners, the GNR, NER and NBR, all became part of the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) while the Royal Scot partners in the west, the LNWR and Caledonian Railway, both became part of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMSR).

In 1924, the LNER officially renamed the 10.00am departures from London and Edinburgh the Flying Scotsman although they had been unofficially known as such for many years. (There were, of course, other daily departures between the capitals but only the 10.00am departures were branded as the FS.) As a publicity gesture, the LNER also named one of their locomotives, a Class A1 Pacific built in 1923 to the design of the GNR’s (and afterwards the LNER’s) Chief Mechanical Engineer, Sir Nigel Gresley, with number 4472, “the Flying Scotsman”. It’s important not to confuse this locomotive with the Flying Scotsman service and to that end I will refer to the loco as “No. 4472”. It regularly hauled the FS but the FS was often hauled by other locos as well. Every loco hauling the FS had a name board on the front saying “Flying Scotsman” so if you see an old picture of a steam locomotive with that on it, it’s not necessarily the famous No. 4472.

Now it would be pleasing to imagine that the LNER’s Flying Scotsman and the LMSR’s Royal Scot competed with each other furiously, vying to be the quickest to Scotland rather like the Transatlantic liners competing for the Blue Riband. But in fact they didn’t. After a few races in the late 19th century, the rival companies settled down to a cosy agreement not to compete with each other on speed (imagine that nowadays - they’d have the Competition Commission all over them before you could say Crewe Junction!) and in the 1920s the Flying Scotsman took a relatively leisurely 8hrs 15mins (an average of 48mph).

That’s not to say the LNER and LMSR didn’t compete at all, however, and, in 1928, the LNER began to schedule the Flying Scotsman as a non-stop service at the height of the summer season. At the time, it was the longest non-stop railway journey in the world and the inaugural non-stop service, on 1 May 1928, was hauled, appropriately enough, by No. 4472. (In summer, there were actually two trains, both departing at 10.00am and designated the Flying Scotsman, but one went non-stop while the other made the usual stops at Grantham, York, Darlington, Newcastle and Berwick.)

It took tens of thousands of litres of water and 9 tons of coal to generate enough steam to drive a heavily loaded train the 392.7 miles between London and Edinburgh. Water could be picked up en route without stopping the train by ingenious means but a specially large tender (fuel truck towed behind the locomotive in front of the coaches) to carry the necessary coal had to be built. There was also the practical point that a single fireman couldn’t shovel 9 tons of coal for more than 8 hours. Hence the tender also incorporated a narrow corridor allowing, for the first time in railway history, communication between the locomotive and the coaches it was hauling so that a relief crew could come forward half way through the journey.

In 1932, the speed limiting agreement between the LNER and the LMSR was scrapped and the time of the Flying Scotsman was reduced to 7hrs 40mins (7hrs 30mins for the non-stop service involving an average speed of 52.4mph). In 1934, No. 4472 made history again by hauling the first train officially recorded to exceed 100mph - not on the Flying Scotsman but between Leeds and London: 100mph was only exceeded over some 600 yards although the average speed over the whole journey was 71mph. The record for the fastest ever steam train, 125mph, was achieved by another LNER locomotive, a Gresley A4 Pacific, No. 4468

Mallard, in 1938 and that class of loco often hauled the Flying Scotsman as well.

The glory days of the Flying Scotsman service, then, were the 1930s but the entire British railway system took a severe battering during the Second World War just as it had during the First. This time, the response was not amalgamation but nationalisation and the LNER and the LMSR (along with the other two private railway companies, the Great Western Railway and the Southern Railway) were absorbed into the state owned British Railways (BR) in 1948.

BR continued to market the 10.00am departures from King’s Cross (KX) and Waverley as the Flying Scotsman (although the non-stop service was dropped in 1950) but by the later 1950s, the days of the steam locomotive were numbered. BR committed itself in 1955 to the phased replacement of steam traction by diesel and electric and the Flying Scotsman began to be hauled by diesel locomotives from 1962. No. 4472 was retired by BR in 1963 and the last BR steam hauled service anywhere on the network was in 1968.

The next big shake up to hit the Flying Scotsman service was the privatisation of BR in the mid 1990s by which time the fastest time between Edinburgh and London was down to 3hrs 59mins. In April 1996, the franchise for services on the East Coast Mainline (ECML) between KX, Leeds and Edinburgh (and on to Glasgow Central, Aberdeen and Inverness) began to be operated by Great North Eastern Railway Ltd (GNER) owned by Sea Containers Ltd, an international shipping company which also owned the Orient Express: GNER continued to market the 10.00am departures from Waverley and KX as the Flying Scotsman.

In late 2006, Sea Containers entered Chapter 11 Bankruptcy in the USA and the British Government terminated GNER’s franchise on the ECML when it threatened to default on outstanding instalments of the £1.3 billion it had paid for the contract. Its place was taken by National Express East Coast (NXEC), a subsidiary of the National Express Group bus company, from December 2007. It continued the tradition of branding the 10.00am service to Edinburgh the Flying Scotsman. NXEC had offered £1.4 billion for the ECML franchise until 2015 but it had bitten off more than it could chew. NXEC suffered losses on the contract during the 2008-09 recession and walked away from the franchise leaving the services to be run from November 2009 by a state owned company called East Coast Mainline Ltd. EC still has a 10.00am departure to Edinburgh (arriving 14.25) but does not, so far as I can see, brand it the Flying Scotsman thus ending almost 150 years of railway history.

As for locomotive No. 4472, on her retirement from BR in 1963 she was saved from the scrap yard by being preserved. She toured America and Australia (where in 1989 she broke her own record of longest non-stop journey by a steam train by extending 393 to 442 miles) and occasionally hauled the Orient Express. But keeping an 80 year old steam locomotive in running order is an extremely expensive business and, having passed through various private owners, No. 4472 was put up for sale again in 2004. Happily, she was acquired by the National Railway Museum at York with the aid of a Lottery grant and a donation from Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Trains (which is a little ironic considering VT are the current franchisees on the Flying Scotsman’s historic rival line, the LMSR’s West Coast Mainline from Euston to Glasgow Central!) She is currently undergoing a comprehensive refurbishment and is expected to be back in commission again during 2010.

And the “Kyles Connection”? Well, it’s a bit tenuous but here goes: if No. 4472, the Flying Scotsman, is the most famous preserved steam locomotive in the world, then the most famous preserved steam ship in the world must be the paddle steamer Waverley. And the connection is that both belonged to the LNER and both are now preserved in their original LNER liveries - red funnel with black top and white stripe for the Waverley and apple green for No. 4472!