I was just trying to see what (if any) impact the Massacre might have had in neighbouring Ballachulish but I found myself wanting to know the full chapter and verse, including buying and reading the book by John Prebble (pictured above) and consulting original contemporary correspondence between the key players available at Archive.org. So I'm just going to write the Massacre up, as much as an aide memoire to myself as anything else.

|

| King James VII & II by Sir Godfrey Kneller |

In 1688, King James VII of Scotland (II of England) was overthrown for the same autocratic and high-handed attitude to government as had cost his father, Charles I, his head. He was replaced on the throne by his daughter Mary and her husband (and also first cousin), William of Orange.

A bit of context about William is necessary. Though his mother was a Stuart princess (sister of Charles II and James VII), he was a Dutchman who held the office of Stadtholder - which was a sort of hereditary president - of the Dutch Republic. Holland was at war with France in a conflict (the Nine Years War) in which England, Scotland and Ireland had hitherto been neutral. The principal theatre of the war was in Flanders. William's main interest in becoming king of the three British kingdoms was to be able to bring them into this war against France, the prosecution of which was his chief pre-occupation.

|

| King William II (III of England) - "William of Orange" by Sir Godfrey Kneller |

In Scotland, not everybody was happy at the irregular change of monarch and some rose in arms in an attempt restore the deposed King James. Prominent amongst these Jacobites, as his supporters were known (from the Latin Jacobus for James), were many of the Highland clans. The rising got off to a flying start with the Jacobite general, Sir John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee ("Bonnie Dundee" but aka "Bluidy Clavers" for his reputation in suppressing Covenanters in the 1670s), scoring a notable victory over the new government's troops at the Battle of Killiecrankie in July 1689. However, Dundee himself was killed at the battle and his successors as generals, Alexander Cannon and Thomas Buchan (who nobody's ever heard of!), failed to press home the Jacobites' advantage and the rising fizzled out after they were defeated at the Battle of Cromdale in April 1690. But there was no formal surrender by the Jacobites or settlement of terms with them: Cannon and Buchan remained at large and they continued to hold castles against the government including Eilean Donan and Duart.

|

| Eilean Donan Castle - held by the Jacobites 1689-92. Picture credit Aidan Williamson |

Meanwhile in Ireland, a much larger Jacobite rising had been taking place. This included those events which reverberate through the consciousness of Northern Ireland to the present day, the siege of Derry and the Battle of the Boyne. By the summer of 1691, the Irish rising was almost over and William was anxious that Scotland also finally be pacified in order that he could return to concentrating on his continental war against France without any Jacobite threats in his rear. But he was also reluctant to commit many troops to Scotland so he instructed his ministers to try to reach a settlement with the Jacobites using a mixture of carrots and sticks.

|

| Sir John Campbell of Glenorchy, Earl of Breadalbane |

In June 1691, the chief of the Campbells of Glenorchy, the Earl of Breadalbane, acting on behalf of the Government held a meeting with the Jacobite chiefs at his castle of Achallader near Bridge of Orchy. Armed with a fund of £12,000 (about £3 million in today's money), ostensibly to buy disputed land in an effort to reduce inter-clan feuds but in reality for distribution as bribes, Breadalbane succeeded in getting the Jacobites to declare a formal ceasefire for three months. At the end of August, the king followed this up with a Proclamation of Indemnity promising a pardon to all rebels who swore an oath of allegiance to him before the end of 1691.

But before the Jacobite chiefs could swear allegiance to William, they had to get James to release them from their oaths of allegiance to him. A messenger was sent to James, now in exile in France, but he delayed releasing the chiefs: as well as being indecisive by nature, he hadn't in late 1691 totally given up hope of renewed action on his behalf in Scotland, aided perhaps by an invasion from France of the Irish Jacobite forces who'd been allowed to withdraw intact to France (the so-called "Flight of the Wild Geese" if you've heard of that) under the Treaty of Limerick which ended the Irish Rising in October 1691. In fact James' permission to his supporters to swear allegiance to William didn't arrive in Edinburgh until 21st December and it didn't reach Lochaber until 28th December, three days before the deadline. The Jacobite chiefs reacted differently: some (including the very influential Cameron of Lochiel pictured below) made haste to take the oath to William in time while others (including the equally influential Macdonell of Glengarry) deliberately held out. One - Macdonald of Glencoe - after being a bit slow off his mark tried to swear timeously but failed.

|

| Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, 1628-1719. Copyright National Galleries of Scotland |

A bit of context is necessary about the Macdonalds of Glencoe as well. The Highland clans had a deserved reputation for feuding amongst themselves and raiding their neighbours' cattle. It was behaviour the 16th and 17th century authorities in Edinburgh deplored but were seldom able to control in much the same way as today's authorities are impotently appalled at periodic outbreaks of violence between present day mafias such as Mexican drug cartels, for example. If you want to know what Argyll and Lochaber were like in the late 17th century, then think Helmand or Sinaloa in the late 20th.

Also known as the MacIains after the Gaelic patronymic of their chiefs, the MacDonalds of Glencoe were a small clan, probably numbering only about 500 souls in total and with a fighting force of about 100-150 men. But though small in numbers, they were among the most egregious of clans where raiding their neighbours was concerned. Then, as now, political disturbance was used as cover for simple criminality. Thus, during the Covenanter wars of the 1640s, the pro-Royalist MacIains, in company with the equally notorious MacDonells of Keppoch, ravaged the Covenanting Campbell of Glenorchy's lands in Breadalbane in two successive years, 1645 and 1646. Again in 1655, the MacIains and Keppochs raided Campbell territory in Breadalbane and Glen Lyon. On each of these occasions, large quantities of cattle and other booty were carried off. In 1685, the suppression of the rising led by the chief of the Campbells, the Earl of Argyll, against the accession of James VII gave cover for reprisals on the lands of various Campbell lairds in southern Argyll. In the course of these the MacIains, along with the Stewarts of Appin as well as their usual partners, the Keppochs, relieved Campbell of Ardkinglas of 1,500 cows and 2,000 sheep and goats. And most recently, on their way back home after the Jacobite setback following the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689, the MacIains and the Keppochs raided Glen Lyon in what John Prebble called "the greatest raid the Lochaber men ever made into Breadalbane."

So MacIain of Glencoe was a man with a lot of enemies when, on 31st December 1691, the last day possible to take the oath of allegiance, he went to Fort William in order to swear it before the Governor there, Colonel Hill. But Hill couldn't administer the oath because, in terms of the Proclamation of Indemnity (read it here), it had to be taken before a civil magistrate and the person MacIain needed to see was the Sheriff-Depute of Argyll at Inveraray, Colin Campbell of Ardkinglas. The history between these two men six years earlier might explain MacIain's decision to leave it so late and go to Fort William but whatever his motive he realised he had to make immediate haste to Inveraray. There was no chance of getting there by midnight when the deadline to take the oath expired but Colonel Hill gave MacIain a letter to Ardkinglas confirming that he'd attempted to swear timeously and recommending the Sheriff-Depute to receive Glencoe "as a lost sheep" and administer the oath, albeit inevitably a day or two late.

|

| As no contemporary pictures of MacIain or Hill exist, we have to make do with stills from a 1971 film which you can see on Youtube here. James Robertson Justice as MacIain - it was JRJ's last film (and MacIain's!) It's pretty wooden but tells the story of the Massacre quite accurately without resort to Braveheart style distortions |

In fact, MacIain didn't meet up with Ardkinglas at Inveraray until 5th January. At first, the Sheriff-Depute demurred at administering the oath though whether because of a grudge he still bore against MacIain for having raided his land in 1685 or scruples about performing his duties to the letter, we don't know. What we do know, because Ardkinglas testified to it to the subsequent enquiry, is that he relented when MacIain pleaded with him to administer the oath in tears. Ardkinglas sent a copy of the oath, with Colonel Hill's letter, to Edinburgh with a request that they be placed before the Privy Council for a ruling on whether the oath had been validly sworn in terms of the Proclamation of Indemnity.

|

| Story in the London Gazette of 14 January 1692 (old style 1691) reporting that Lochiel, Keppoch and Stewart of Appin, amongst others, had sworn oaths of allegiance. |

MacIain returned home from Inveraray to Glen Coe in the belief all was well. But it wasn't. For if people like Colonel Hill of Fort William and Campbell of Ardkinglas had been prepared to take a lenient view of MacIain's lateness in submitting, his case had not been placed before the Privy Council and the most powerful man in Scotland, the Secretary of State - effectively the prime minister, although that office didn't exist then - Sir John Dalrymple, Master of Stair, had other ideas.

|

| The Master of Stair - if any Scottish lawyers are reading this, he was the son of the Lord Stair who wrote the Institutions. (Only a Scottish lawyer knows what that means.) |

Stair was determined to use failure to swear the oath of allegiance to King William by the deadline on 31 December 1691 as a pretext to teach some unruly clans a lesson they would never forget. The MacDonalds of Glencoe and their partners in crime, the egregious MacDonells of Keppoch, were firmly in Stair's sights but at first it looked as if he might be disappointed after early reports from the north suggested that both of these clans had sworn in time. This emerges from a letter (read it here) he wrote to the Commander in Chief of the army in Scotland, Sir Thomas Livingstone, on 9 January in which Stair said: "I am sorry that Keppoch and M'Kean of Glencoe are safe." In fact, Keppoch had indeed sworn in time but two days later Stair received better news and had the consolation of being able to write (here - page 62) to Livingstone:-

Just now my Lord Argile tells me that Glenco hath not taken the oathes, at which I rejoice, it's a great work of charity to be exact in rooting out that damnable sept, the worst of all the Highlands.

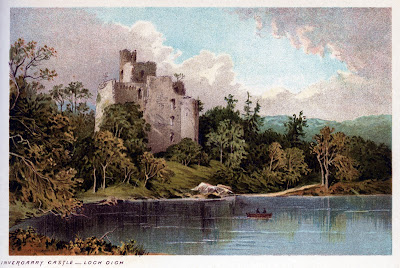

Meanwhile, the primary target amongst the hold out clans who had not sworn allegiance was the MacDonells of Glengarry. Apart from anything else, the government wanted their castle at Invergarry (below) for a garrison at a point mid way between Fort William and Inverness, the role fulfilled by Fort Augustus after 1715.

|

| Due to now being almost totally surrounded by tall trees, Invergarry Castle is more easily seen in this Victorian chromolithograph than a modern photo: Picture credit pastpin |

When Invergarry surrendered in the second half of January, government forces were freed up to execute Stair's plan to destroy the MacDonalds of Glencoe. On 1 February 1692, a company of 120 men of the Earl of Argyll's regiment was despatched to Glen Coe under the command of Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon - yes, that Glen Lyon, the one subjected to "the greatest raid ever into Breadalbane" by the MacIains and Keppochs three years earlier. But Glenlyon didn't at this stage know the nature of his mission and for now his orders were simply to quarter his men on the people of Glen Coe. That meant live with and be fed by them free of charge due to Fort William being full. Quartering was an accepted fact of life at the time so the MacDonalds were not unduly perturbed by the arrival of the soldiers and, as is well known, accepted them hospitably into their homes without rancour. And just to show there's nothing black and white where clans are concerned, Glenlyon's niece was married to MacIain's second son so there was a bit of a family reunion to be had. And despite the fact that he'd been so recently financially ruined by the great raid of his lands, he passed many of his evenings in Glen Coe amicably drinking and playing cards with MacIain's sons: it's been suggested Glenlyon held Keppoch more than MacIain primarily to blame for the raid.

|

| Robert Campbell of Glenlyon was 60 at the time of the Massacre of Glencoe. This is him as a young man. |

On 12 February 1692, a cascade of new orders were issued. The Deputy Governor of Fort William, Lt. Col. James Hamilton, instructed Major Robert Duncanson of Argyll's Regiment camped at North Ballachulish to cross Loch Leven to Glen Coe and join Glenlyon in the execution of orders against the MacDonalds of Glencoe. These (read them here) included that:

none be spared, nor the government troubled with prisoners

Duncanson was to do this at 7 o'clock sharp the following morning and, in wording which looks like it's giving him cover for conveniently not getting there until after the dirty work had been done, Hamilton told Duncanson he would "endeavour" to get from Fort William via Kinlochleven to the east end of Glen Coe at the same time to cut off the MacDonalds' escape in that direction.

Duncanson in turn wrote to Glenlyon, ordering him to

fall upon the rebells, the M'Donalds of Glenco, and to putt all to the sword under 70.

In an even more blatant attempt at shielding himself, Duncanson ordered Glenlyon to act at 5 o' clock the following morning, precisely. Duncanson would "strive", he said, to get there by 5.00 to assist but Glenlyon wasn't to wait for him. In the event, Duncanson didn't arrive on the scene until 7.00am when it was all over, thereby complying with his orders from Hamilton but avoiding getting any actual blood on his hands. And Hamilton's party didn't arrive until 11 o'clock.

|

| Looking east up Glen Coe. The killings took place in the floor of the valley at bottom right. Picture credit Oscar Garcia |

The Massacre of Glencoe is usually portrayed as just another act in the perennial feud between the MacDonalds and the Campbells and with the latter for once getting the chance to give the former a taste of their own medicine. But although the Massacre was carried out by men of the Earl of Argyll's regiment under the command of a Campbell, only about a tenth of them had the name Campbell and we cannot know or assume the clan allegiance (if any) of such of the remainder as appear from their names to have been Highlanders. While Glenlyon did not refuse his orders, and he put them into execution at 5.00am prompt as instructed, there is some anecdotal evidence that the worst of the killing was carried out by Lowland soldiers who viewed their erstwhile hosts with contempt, not for being MacDonalds, but simply for being Highlanders whom the lowlanders tended to regard generally as worthless barbarian savages. Thus, for example, and although it hardly goes very far towards redeeming him, it was said that a boy of about 12 ran to Glenlyon begging for mercy. When he appeared minded to spare the lad, a Lowland officer, Captain Drummond, impatiently reminded Glenlyon of their orders to spare nobody under 70 then shot the boy.

Anyway, the generally accepted number of people killed before dawn on 13th November 1692 is 38. These included MacIain himself but not his two sons John and Alexander whom Duncanson and Glenlyon had both been enjoined in their orders not to let escape. It's not clear whether this 38 dead includes the two women, two children, a boy of about 12 or 13 and two old men mentioned by witnesses to the subsequent Commission of Enquiry as having been killed. It certainly doesn't include those who must inevitably have died of exposure as they fled into the surrounding mountains.

The aftermath - Royal Commission and Parliamentary Enquiry

Were it not for the fact that it was perpetrated by guests upon their hosts as they were asleep in their beds, the action by the Government against the MacDonalds of Glencoe would probably not occupy more than a sentence or two in the history books. Whilst it may have been harsh to single out the MacIains for having sworn allegiance just a few days after the deadline when other holdout clans who didn't submit till much later were spared, the episode would probably have been largely dismissed as a measure pour encourager les autres if only it had been carried out, to quote the subsequent Commission of Enquiry, "by fair hostility". Commander-in-Chief Livingstone captured the mood when he wrote to Lt. Col. Hamilton in May 1693:-

It is not that any body thinks that thieving tribe did not deserve to be destroyed, but that it should have been by such as was quartered amongst them, makes a great noise.

In fact, Livingstone's letter to Hamilton (read it here) was in the context of a possible Parliamentary enquiry into the Massacre. But this never got off the ground. The time was not yet right politically. However, things had changed by 1695 when Stair was now politically on the defensive. His enemies were determined to use his role in the Massacre to attack him and they induced King William to order a Commission of Enquiry.

|

| John Hay, 1st Marquess of Tweeddale who presided over the 1695 Royal Commission of Enquiry into the Massacre of Glencoe. Picture credit National Galleries of Scotland |

Many of those involved gave evidence to the Commission including John MacDonald, the late MacIain's son and now chief of the MacDonalds of Glencoe, his brother Alasdair and three of their clansmen; Colonel Hill the Governor of Fort William; Colin Campbell of Ardkinglas (who administered the oath to MacIain six days late); Private Campbell of Glenlyon's company (who testified to seeing other soldiers killing people but not, naturally, to killing anybody himself); and Major Forbes and Lieutenants Farquhar and Kennedy of Lt. Col. Hamilton's party (which had approached Glen Coe from the east via Kinlochleven but arrived so late that, in the words of the Commission "there remained nothing to be done by [Hamilton], and his men, save that they burnt some houses, and kill'd an old man"). There seems to be a conflict of opinion on whether Hamilton himself testified but the Commission definitely didn't hear from Major Duncanson, Glenlyon or Captain Drummond who shot the boy Glenlyon had been minded to spare because they were all with their regiment in Flanders.

|

| The Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh where the Royal Commission sat in May and June 1695. Picture credit Elena Kazantzanidou |

A "barbarous murder" was how the Commission categorised the events of 13 February 1692 in its Report to the King but who had ordered it? And how deeply involved was King William personally?

The Commission found that, in response to the fact that some of the Jacobite clans had not sworn allegiance to him by the appointed day on 31st December 1691, the King signed orders in London dated 11th January 1692 to his Commander-in-Chief in Scotland, Sir Thomas Livingstone. You can read them here. Livingstone was ordered to:-

march our troops, which are now posted at Inverlochy [i.e. Fort William] and Inverness, and to act against these Highland rebells who have not taken the benefite of our indemnity, by fire and sword, and all manner of hostility; to burn their houses, seiz or destroy their goods or cattell, plenishing or cloaths, and to cutt off the men.

It sounds draconian but this was really just a stereotyped form of words authorising military action against the holdout clans (as opposed to, say, pursuing a policy of doing nothing or continuing to negotiate etc.) which the Commission considered the King was quite within his rights to do. And the order was mitigated by William also ordering Livingstone that chiefs who swore allegiance might be spared their lives upon being taken prisoner and forfeiting their lands while their clansmen ("yeomen and commonalty") could go free and also keep their property if they submitted.

|

| Sir Thomas Livingstone, Commander in Chief of the army in Scotland in the 1690s. |

These orders were sent to Livingstone by Stair who was with the King in London. He also copied the orders to the Governor of Fort William, Colonel Hill, but back in December Stair had previously arranged with Livingstone that the officer primarily responsible for action against such of the Lochaber clans as did not submit would be Hill's deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton. This was partly due to the fact that Hill was elderly and in poor health but also, no doubt, because Hill was known to be sympathetic to the clans, even such incorrigibles as the MacIains and Keppochs, and might not have had the stomach for the sort of stern measures against them Stair was planning.

On 11th January, Stair discovered that, contrary to his earlier understanding, the MacDonalds of Glencoe had not in fact sworn allegiance by the deadline on 31st December. This, therefore, necessitated additional orders which the King signed on 16th January. They are here and, after dealing with other matters and repeating that anyone who took the oath of allegiance should be spared, contained the key order:-

4. If M'Kean of Glencoe, and that tribe, can be well separated from the rest, it will be a proper vindication of the publick justice to extirpate that sept of thieves.

The Commission interpreted that obscurely worded sentence to mean that William understood that MacIain had not yet taken the oath of allegiance and that, if he continued to refuse to do so (thereby "separating himself from the rest" of the holdout clans who were assumed to be all going to submit shortly), his clan were, in the words of the Commission: "only to be proceeded against in the way of publick justice and no other way." If that seems a rather charitable interpretation of the word "extirpate", it was hardly to be expected that the Commission was going to point any fingers of blame too directly at the King. I think what William meant by "extirpate" was that the MacIains were to be utterly destroyed as a fighting force such that they could never again trouble their neighbours: that might involve a more root and branch aassault than would be sufficient to neutralise them solely in the context of ending the Jacobite rebellion but it was still be in "fair hostility". I don't think His Majesty was ordering the MacIains to be murdered in their beds.

|

| Glen Coe in winter - Picture credit Ed Daynes |

Thus was the King acquitted of responsibility for the Masscare of Glencoe. What of his minions?

It's important to understand that, up till this point, in the middle of January, neither the King, Stair nor Livingstone knew that MacIain had taken the oath of allegiance but late. They all thought he hadn't sworn at all and the orders for action against his clan were on the assumption that he continued to refuse to submit. But that soon changed for, on 23rd January, Livingstone wrote (here) from Edinburgh to Hamilton at Fort William in terms which showed he knew MacIain had already sworn, albeit late:

Since my last [letter to you on 18th January] I understand that the Laird of Glenco, coming after the prefixed time, was not admitted to take the oath, which is very good news here, being that at Court it's wished he had not taken it, so that that thieving nest might be intirely rooted out; ... I desire you would begin with Glenco, and spair nothing which belongs to him, but do not trouble the Government with prisoners. [emphasis added]

Thus did Livingstone disobey his instructions from the King by ordering Hamilton to take no prisoners from the MacDonalds when he knew that MacIain had taken the oath.

Hamilton promptly ordered Glenlyon's men into Glen Coe but there was a problem - Colonel Hill. Although opposed to what was afoot - as he expressed it in his testimony to the Commssion, he "liked not the business, but was grieved at it" - Hill still had to be given his place in the military chain of command and nothing could be done against the MacDonalds without his order. But he couldn't bring himself to give it. The attack would probably have started immediately the soldiers arrived in the glen on 1st February but the Colonel's prevarication meant they had to take up their quarters and wait. Eventually, on 12th February, Hill attempted, rather unconvincingly, to square his conscience by simply authorising Hamilton to execute the orders he (Hamilton) had already received from Livingstone.

|

| The Pass of Glen Coe from the east. Hamilton's party, minus two officers who'd refused to take part, approached from Fort William down the hills on the right. Picture credit David Galloway |

The Commission's final report dated 15th June 1695 didn't allocate responsibility for the Massacre of Glencoe to any individual but the Master of Stair did not come out of it well. In particular, they highlighted a letter Stair had sent to Livingstone on 30th January, before the Massacre took place, which they claimed proved Stair knew that MacIain had taken the oath, albeit late, yet still egged the Commander-in-Chief on to "rooting out and cutting off that thieving tribe" contrary to the King's orders. But what Stair said in the letter was "I am glade that Glenco did not come in within the time prescribed." That is equally consistent with a belief that Glencoe had not come in at all. In other words, he does not say "I am glad that Glencoe came in after the time prescribed." These and other points in Stair's defence were made in a document circulated by his friends you can read here. Putting on my legal hat, if I were a juror I think I'd have to return a verdict of "not proven": there's no evidence he knew MacIain had taken the oath. The same cannot be said in defence of Sir Thomas Livingstone, though. Nobody's ever heard of Livingstone yet I think he is at least as guilty as Stair if not - as a military officer who disobeyed his orders - more so.

Next, Parliament debated the report. It immediately passed unanimous motions declaring the Massacre to be murder but exonerating the King and then moved on to debating who it considered to be guilty. In an address to his Majesty dated 10th July 1695, the Master of Stair's letters were declared to have exceeded the King's orders and to have been "the original cause of this unhappy business". Parliament tactfully suggested that His Majesty "give such orders about [Stair], for vindication of your Government, as you in your royal wisdom shall think fitt."

Sir Thomas Livingstone, the Commander-in-Chief, must have had powerful friends because he was exhonerated, Parliament accepting that he did not know MacIain had sworn allegiance even though his correspondence clearly showed that he did. They also found Colonel Hill, the Governor of Fort William, to be innocent, his evasive order to his deputy, Hamilton, merely to follow the orders he (Hamilton) had received from Livingstone being regarded as enough to absolve him.

Hamilton - who'd absconded and failed to appear before Parliament - was found "not clear of the murder of the Glencoe men and that there was ground to prosecute him for it". Major Duncanson of the Earl of Argyll's Regiment who'd received orders from Hamilton and in turn ordered Glenlyon to fall upon the MacDonalds before dawn on 13th February 1692 was in Flanders with his regiment and Parliament had not seen the orders he'd either received or given - they therefore recommended to the King that Duncanson either be questioned in Flanders or sent home for prosecution as His Majesty thought fit.

As for Glenlyon and the junior and non-commissioned officers under his command, they too were in Flanders but Parliament was satisfied that they were all "actors in the slaughter of the Glencoe men under trust" and the King was requested to send them home "to be prosecuted for the same according to law".

|

| Parliament Hall in Edinburgh where the Scottish Parliament debated responsibility for the Massacre of Glencoe in July 1695. The stained glass wasn't there in 1695 but the ornate ceiling was. |

Anybody else?

It's the Master of Stair that's usually remembered as the orchestrator of the Massacre of Glencoe - the man who used political turbulence as a pretext to exterminate a clan who were criminals but not enemies of the state. But what made someone with no vested interest - Stair owned no estates in areas vulnerable to predation by the likes of the MacIains or Keppochs - suddenly becme such a champion of law and order in the Highlands? Might the real architect of the Massacre have been someone who did have that vested interest and gave Stair the idea. A circumstantial case can be made for that person being the John Campbell of Glenorchy, the Earl of Breadalbane.

Breadalbane had land close to Glen Coe and MacIain's sons testified to the Royal Commission that, at the meeting at Achallader in June 1691 to negotiate the Jacobite ceasefire, there had been a quarrel between their father and the Earl over stolen cows and that MacIain had told them that Breadlbane "threaten'd to do him a mischief". The MacDonald brothers also told the Commission about an odd episode in which, a few days after the Massacre, Breadalbane's steward came to them with an offer that, if they wrote a letter clearing the Earl of any involvement in it, he would use his influence to procure their "remission and restitution".

In his book, John Prebble noted a ramping up of the invective against the MacIains in Stair's correspondence after a meeting he'd had with the Earl of Argyll and Breadalbane on 7th January 1692. And finally, and to my mind the most telling evidence, is that Stair informed Colonel Hill in a letter of 16th January that these Earls had agreed not to allow the MacIains to retreat into their lands surrounding Glen Coe.

Neither the Commission nor Parliament considered Breadalbane's possible involvement in the Massacre because he was not in the political or military chain of command. But for those who suspect he may have had a hand in it, it's poetic justice that the proceedings before the Commission incidentally revealed that he'd been been double dealing with the Jacobites at Achallader with the result that Breadalbane was arrested and incarcerated in Edinburgh Castle on charges of treason.

|

| The reliably photogenic ruins of Kilchurn Castle, one of several owned by the Earl of Breadalbane. The lower range of buildings and towers on the left were built by the Earl in 1690 in one of the last ever exercises in private fortification in Scotland. Picture credit Wallace Shackleton |

What became of everybody?

Despite Parliament's recommendations to the King, nobody was ever prosecuted for the Massacre of Glencoe.

Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon died a year later, in 1696, in Bruges. Ironically, his heir, John Campbell of Glenlyon led his clansmen out in both the 1715 and 1745 Jacobite Rebellions.

Major Robert Duncanson, who'd ordered Glenlyon to fall upon the MacIains, was arrested when he returned to Scotland in 1697 but for debt rather than "barbarous murder". He eventually returned to the army and died in 1705 at the Siege of Valencia de Alcantara during the War of the Spanish Succession, the colonel of his own regiment.

A month after Parliament had determined he ought to be prosecuted, Lt Col. Hamilton, the Deputy Governor of Fort William, turned up at the King's camp in Flanders to throw himself on William's mercy - but nothing seems to have come of this and vanished into obscurity.

Hamilton's superior, the conscience stricken Colonel Hill, remained as Governor of Fort William until 1698 when he finally retired on half pay.

The Commander-in-Chief, Sir Thomas Livingstone, who disobeyed the King's orders by prosecuting the MacDonalds of Glencoe in the knowledge that they had taken the oath, was promoted to the peerage as Viscount Teviot in 1696. He ended his military career a Lieutenant-General in 1703 and died in 1711. His estranged wife was accused but acquitted of having poisoned him. He's buried in Westminster Abbey.

|

| Sir Thomas Livingstone, Viscount Teviot's memorial in Westminster Abbey. Picture credit - Westminster Abbey |

There's no monument to the only two men on the Government's side to come out of the Massacre of Glencoe with their consciences entirely clear and honour intact - two lieutenants in Hamilton's party which marched from Fort William to the east end of Glen Coe and got there after it was all over. Possibly the Gilbert Kennedy and Francis Farquhar who gave evidence to the Commission, they refused to take part and were arrested by Hamilton for their trouble.

The treason charges against the Earl of Breadalbane were eventually dropped but the authorities had been right to suspect his loyalty: he sent 500 of his clansmen to join the Jacobites in 1715 but escaped punishment again by dying the following year.

The Master of Stair deemed it prudent to resign as Secretary of State in the wake of the parliamentary enquiry but this was very much in the nature of a tactical temporary withdrawal rather than any admission of culpability. The orders the King gave about him "for vindication of Government" were probably not quite what Parliament had had in mind in its address to William: he issued a "Scroll of Discharge" to Stair (now Viscount Stair since the death of his father, the famous lawyer, in November 1695) exonerating him from any responsibility for the Massacre in respect that he "being at London, many hundred miles distant, he could have no knowledge of, nor accession to, the method of that execution". Stair subsequently made a political come back during the reign of Queen Anne and was promoted to Earl of Stair.

In 1697, King William II & III's war against France ran out of steam but he secured pretty reasonable terms at the Peace of Ryswick including recognition by France of himself rather than the deposed James VII & II as King of England, Scotland & Ireland. James never recovered his thrones: he died in 1701 and William the following year.

|

| MacDonald of Glencoe burial enclosure on Eilean Munde - Picture credit James Lynott |

As for the MacDonalds of Glencoe, in the immediate aftermath of the Massacre they lived as fugitives in the surrounding mountains until that August, 1692, when, through the intercession of Colonel Hill, they were allowed to return to rebuild their homes in the glen. They had obviously prospered enough that, by 1708, the new chief, the murdered MacIain's son, John, had built himself a new house to replace his father's burnt by Glenlyon's men. That house no longer stands but a dated and monogrammed pediment from it is preserved in the wall of the MacDonalds' burial enclosure on Eilean Munde in Loch Leven pictured above. They remained incorrigible Jacobites, though, and were "out" in both the 1715 and 1745 Rebellions.

An Irony?

Retribution against against Highland Clans in the course of the suppression of Jacobite risings - of which the Massacre of Glen Coe and the reprisals in the months following the Battle of Culloden are examples - are, together with the Highland Clearances, often seen as key events in a wider campaign of suppression by outside agencies of Highland culture as whole. It may not be uncoincidental that these were the topics of John Prebble's best selling trilogy. But there is a ghastly irony here which I'm grateful to historian and tour guide Andrew Grant MacKenzie for drawing to my attention. In this article, Andrew describes how Alexander MacDonald, the 16th Chief of the MacDonalds of Glencoe and the murdered MacIain's great great grandson who owned Glencoe Estate from 1787 to 1814 was a sheep-farmer on a massive scale. As I understand it, MacDonald didn't practice sheep farming in Glen Coe but he did on a truly vast portfolio of land, including as far away as Loch Luichart in Ross-shire, he rented from third parties. It's kind of hard to believe MacDonald didn't perpetrate any clearances on native tenantry in pursuit of this collossal farming enterprise. It eventually collapsed under its own weight and certainly came back to haunt the tenantry (it would be anachronistic to call them clansmen) in Glen Coe when, to raise money to settle his debts after his death in 1814, MacDonald's trustees had to raise the tenants' rents ruining many of them. What an irony that the work left undone by Campbell of Glenlyon and his superiors in 1692 ended up being continued a century later by the MacIains' own chief!

|

| Memorial in Glen Coe. Picture credit Jacobite52 |

Thanks Neil for another informative, educational and enjoyable read. And the perfect length for enjoying with a cup of tea too!

ReplyDeleteThank you Roy. That's very kind of you to say so particularly considering I think my posts end up being far too long and any merit they may have had at the start is lost by readers glazing over!

Deletexcellent...

ReplyDelete