I do. It is, I can say without a moment's hesitation, the A87 - the road that runs from Invergarry on the A82 in the Great Glen to Kyle of Lochalsh then across to Skye and ending at Uig, the ferry terminus for Harris and the Uists, 98 miles away.

It's my favourite road because it's the one where you turn west to take you deep into the North West Highlands. The A87 used to be (just before my time, unfortunately) where the single track roads began and it takes you to some of the most impossibly evocatively named places in Scotland - Kinloch Hourn, Kintail, Stromeferry, Plockton, Kyle of Lochalsh, Sligachan, Portree ...

It also ticks a lot of my boxes because most of it was built by the Highland Roads and Bridges Commission in the early 19th century (partly replacing an earlier military road). There are original HRBC bridges to be seen (Shiel Bridge), early 19th century wayside inns still in business along its length (Cluanie, Sligachan) and it runs past castles (Eilean Donan) and a Jacobite battle site (Glenshiel) not to mention numerous estates, lodges and manses. More recently, there's stuff flooded by mid 20th century hydro-electric developments, old ferry crossings now bridged, ghost junctions and by-passed but still driveable lengths of single road track road - in fact the A87 has had its route considerably altered (and greatly lengthened) over the years in consequence of successive improvements during the 20th century to accommodate ever increasing motor traffic demands. So this is the first of a series of posts about stuff that interests me along the A87 but be warned - stuff that interests me doesn't necessarily interest everyone!

First, the village of Invergarry.

|

| Approaching Invergarry on the A82 from the south - Google Streetview |

|

| A MacBraynes paddle steamer sails north up Loch Oich. The mouth of the River Garry is visible on the right. |

|

| Invergarry Station in its heyday. Note the sloping roof of the entrance to the underpass under the further track - it all seems pretty over-engineered for such a marginal branch line! Picture credit - Freetalk1 |

|

| Invergarry Station today with the buildings all gone. The village is on the other side of the loch approximately opposite the islands in the distance. Picture credit - The Loose Canon |

There's lots more interesting information about Invergarry Station with pictures then and now here.

|

| Invergarry Castle from above. Picture credit - Sean Ruddy |

Many castles look very impressive with turrets and battlements and whatnot but never saw a day's action in their life. Not Invergarry, though, which has literally been through the wars almost since the day it was built in the mid-17th century (which is pretty recently as castles go). In 1654, "Glengaries new house" (i.e. castle) was burnt and the remaining structure "defaced" in the aftermath of the ill-fated Glencairn Rising (a Royalist rebellion against the Cromwellian occupation of Scotland). It was repaired around 1670 but Glengarry's Royalist sympathies mutated into Jacobitism and the castle was besieged by Government forces during the 1689 Rising (Bonnie Dundee, Killiecrankie etc.) and taken in 1692. It then became a Government garrison until the 1715 Jacobite Rising during which Glengarry laid siege to his own castle on behalf of the rebels and seized it. In the wake of the collapse of that rebellion in 1716, though, it was accidentally burnt by the Government soldiers who had re-occupied it. The Government built Fort Augustus instead and Invergarry Castle lay empty until it was repaired again in the 1720s. After a period of occupation by an English iron-master called Thomas Rawlinson who was using the local forests for fuel for iron smelting (more about that here), Glengarry resumed residence in 1731.

The MacDonells were out for the Jacobites again in the 1745-46 Rebellion although their regiment was led by the chief's son Angus while the chief himself stayed out of things in the interests of "it wisnae me" deniability. Bonnie Prince Charlie spent a night at Invergarry Castle in August 1745 on his march south from Glenfinnan to Edinburgh. He also spent part of the first night after the Battle of Culloden there but Old Glengarry was not at home - he was in Inverness protesting his loyalty to the Duke of Cumberland but that didn't prevent the castle being burnt in May 1746 on the latter's orders. It was never rebuilt and the MacDonells moved to a new house built around 1760 about a quarter of a mile to the north.

|

| MacGibbon & Ross's "The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the 12th to the 18th centuries, Volume III, page 620 |

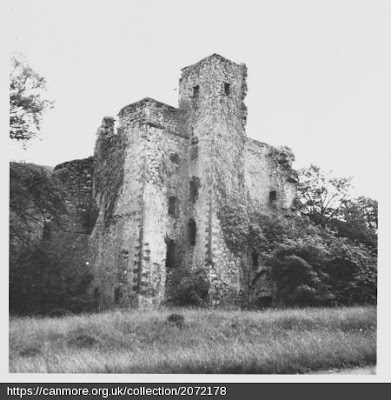

In plan, Invergarry Castle was an L-plan tower of five stories with an oblong stair tower in the angle and a round stair tower at the north-east corner. Most of the north west wing (top left of the plan) collapsed long ago. The oblong stair tower in the angle was still standing until the second half of the 20th century as can be seen from the picture below taken in 1952 (viewed from top right of the plan):-

|

| Oblong stair tower still standing in 1952. Picture credit - Canmore, larger resolution image here |

... but it has since collapsed in big lumps as you can see in the photo below taken from the same angle:-

|

| Stair tower collapsed. Picture credit - Keith Fraser |

These last two photos are both from roughly the same angle as the conjectural view of the castle when complete further up (from the top right of the plan). Due to its very unstable curent condition, you can't go inside Invergarry Castle but you can go for a virtual walk past it here.

|

| The ruin of Invergarry Castle with the house built around 1760 the Glengarrys lived in latterly seen in 1840. Picture credit - National Libraries of Scotland Maps |

Glengarry had been en route to Edinburgh to consult his lawyer about his debts which, thanks to an extravagant lifestyle beyond his means, amounted to a staggering £80,000 - about £9 million in today's money. This was despite the annual rental of the Glengarry estates having increased from £700 in 1761 to £5,000 in 1800 (about £400,000 today) through a ruthless policy of clearing clansmen and re-letting their land to southern sheep farmers at much higher rents: according to one source, on farms where once there had lived 1,500 people, there now (1820s) lived only 35.

But do the math and the enhanced income barely covered the interest on the debt never mind portraits by Raeburn so Alasdair Ranaldson's heir's trustees decided there was no option but to sell up. The east end of the estate including Invergarry (about 56,000 acres/23,000 hectares outlined on this map) was sold to the Marquis of Huntly in 1836 with the MacDonells retaining for now Glenquoich (pron. "Glen KOO-ich" - green on this map) and Knoydart on the west coast. In 1840, Glenquoich was sold for £32,000 to Edward Ellice, a wealthy Canadian of Scottish ancestry involved in the fur trade (bio of Ellice here and more about Glenquoich Estate here). The same year Huntly, having been declared bankrupt, sold his estate to Lord Ward for £91,000. Also in 1840, Glengarry, emigrated to Australia but returned after a few years to settle on the only remaining bit of his family's ancient patrimony, Knoydart, where he died in 1851. His heir, another Alasdair, sold Knoydart in 1853, the purchaser making it a condition that all the remaining crofters - 400 people - be removed in one of the last but grimmest episodes of the Clearances. MacDonell, now just the owner of the ruin of Invergarry Castle and the family mausoleum at Kilfinnan on Loch Lochy, then emigrated to New Zealand never to return. Finally, in 1860, Edward Ellice's son, another Edward, bought Invergarry Estate from Lord Ward for £120,000 (about £15m today) so that, when he inherited Glenquoich upon his father's death in 1863, Edward Ellice, Jnr. became the owner of the whole of the former MacDonell of Glengarry estate except Knoydart.

|

| Invergarry House |

In 1869, Edward Ellice, Jnr. commissioned a magnificent new mansion house from the Scottish architect David Bryce on the site of the previous house of the 1760s which had been described in the 1850s as being in a "rather ruinous state". In Bryce's signature yellow sandstone with corbelled out "cheekbones" between the bay windows and pediments above (see another example of this in Edinburgh here) and with its own gas-works (here), all that the new house retained from the time of the MacDonells was a Carron Ironworks fire grate of 1760 (picture of that here) and the "formal avenue of trees down to the lake" (Loch Oich) a traveller in 1800 remarked upon and pictured below:-

|

| Picture credit jojomiguel via Tripadvisor |

Since 1958, Invergarry House has been the Glengarry Castle Hotel and if you can't afford to stay there, you can go for a virtual walk past it here.

Beyond the "big house", Invergarry is a typical estate village created by the Ellices in the second half of the 19th century. Prominent is the Invergarry Hotel, pictured below, built in 1885 to replace an older inn on the same site: Burns buffs will be interested to know that the bard's friend, the carpenter said to have made his coffin and eponym of his song "John Anderson, my Jo", lived here in the 1830s with his daughter and her husband who was the inn-keeper (and who by coincidence also died in a steamboat accident, this time the Comet II at Gourock in 1825 while on passage between Inverness and Glasgow via the Caledonian Canal).

|

| Invergarry Hotel (1885). Picture credit - Highland Living |

|

| Invergarry in 1871 as seen on the Ordnance Survey 6 inch map. Click to enlarge. |

Other buildings built by the Ellices in Invergarry as the infrastructure of their estate included a church (1864, by the very prolific Inverness architect Alexander Ross who's best known work is probably Duncraig Castle at Plockton), a school (1868), a bank, a cottage hospital (1880, by John Rhind who also designed the hotel), the factor's lodge (estate manager's house - 1870), a shop and mill (the latter predating the Ellices but nevertheless having their signature porch) and post office as well as a number of estate workers' cottages (for example here and here) and even almshouses for retired workers. Many of these buildings bear the Ellice crest (as seen on the hotel here), most are listed buildings and with the whole set amongst ornamental trees such as copper beeches, yews and monkey puzzles, I'm surprised the village isn't a conservation area.

The Ellice family still owns about 17,000 acres of the east end of Glengarry Estate although Glenquoich and a lot of the west end of the Invergarry section of the estate was sold off in the 1940s, much of it to the Forestry Commission. Nowadays, they call their estate Aberchalder & Glengarry Estate (here) reflecting the shift in its centre of gravity eastwards to being centred on Aberchalder Lodge at the north end of Loch Oich.

Well, these are just some of the things that interest me around

Invergarry and we haven't even turned on to the A87 yet! I'll remedy

that in the next post.

|

| Invergarry House (now Glengarry Castle Hotel). Aberchalder Lodge is the white house on the far side of the loch |

Excellent! The first of a series of inbound articles on what is also happens to be my favourite trunk road.

ReplyDeleteAnd on the subject of inbound… Invergarry and environs would have been a first-strike nuclear target if plans for an experimental ballistic submarine communications system had progressed in the early 1990s. It would have seen the erection of an aerial of up to 150 miles in length along Glengarry. Fortunately, the end of the Cold War meant that the project never got beyond the planning phase.

As for the "over engineered" underpass ramp shelter at Invergarry Station, I predict that your article on the I&FAR will contain the phrase 'over engineered' many times over!

Hi Neil, Marylaura Henderson here! It's been very interesting reading your article about Invergarry and the MacDonells. Shortly after purchasing Tomdoun Hotel I discovered that I am a direct descendant of the 11th chief, Alasdair Dubh, died 1721. That's where my son Alasdair born April 1981 got his name from.

ReplyDeleteWow! I think you can legitimately describe yourself as a true Highlander then!

Delete